A digestible problem

A young physician remembers army surgeon Dr. William Beaumont, his patient Alexis St. Martin, and the study of gastric secretions.

Alex Istor had never intended to be a physician. His father, an officer in the army, had dreamt that his son would one day follow in his footsteps. But as a boy Alex had resisted the paternal prodding. In an attempt to persuade him, his father showed him countless military documentaries and films. These efforts fell short of inspiring him to enlist and instead sparked an insatiable interest in history. By his junior year of high school, Alex had decided to become a history professor. He was accepted into Cornell University and began his studies with a focus on military history.

During Alex's senior year, his father was diagnosed with metastatic gastric cancer. Alex was stunned by this news. He watched his father suffer before he passed away soon after Alex's college graduation.

Distraught, Alex began to question his path in life. He lost interest in his history studies and decided abruptly to pursue a career in medicine. After completing the prerequisite courses, he was accepted to medical school. He excelled, graduating near the top of his class before accepting a medical residency in Buffalo, N.Y. Part of his training involved working at the regional VA. He found satisfaction caring for veterans who reminded him of his father.

One day, Alex was rotating on a busy inpatient service and had just finished rounds when he was paged to see a patient in the emergency department. It was a 74-year-old Army veteran, Mr. Martin. He had been in his usual state of health up to three months ago when he noticed problems with his balance and had fallen twice. The only medical issue he had was long-standing dyspepsia, and more recently some tingling in his feet. He took no medications and reported no alcohol use. He had not seen a doctor since his days in the service more than 40 years ago.

Alex reviewed the ED workup, which included a normal CT scan of the head, and basic laboratory testing, which was notable for macrocytic anemia. He examined Mr. Martin, noting significant ataxia, conjunctival pallor, mild epigastric tenderness, and a loss of vibratory sensation in his feet. He admitted Mr. Martin and ordered more extensive testing. Alex was somewhat surprised when additional labs indicated that Mr. Martin had deficiencies of both iron and B12. Suspecting a problem with gastric function, he ordered an anti-intrinsic factor antibody level and esophagogastroduodenoscopy. He finished up his remaining work and headed home to rest.

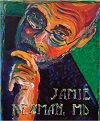

As Alex was lying in bed that night, the name “Martin” nagged him. It seemed familiar in some odd way. Then he remembered a medical history lecture he'd attended while studying at Cornell. The talk was about army surgeon Dr. William Beaumont, his patient Alexis St. Martin, and the study of gastric secretions. He recalled the details as he drifted to sleep.

In 1822, Dr. Beaumont had been tasked with treating Alexis St. Martin, who had been shot in the stomach while working for a fur trading company. Although St. Martin's prognosis was grim, he survived, but not unscathed. When his wound healed, a fistulous tract developed between his stomach and abdominal wall. As a curious scientist, Dr. Beaumont jumped at the opportunity for an unprecedented study of gastric physiology. At first St. Martin was a willing participant. Dr. Beaumont began his experimentation by inserting bits of food tied to string though the fistula and into the stomach. After varying periods of time, he would pull them out and observe the effects. The longer he left the food bits in St. Martin's stomach, the more breakdown of the food he observed. His studies intensified, so much so that St. Martin fled to escape further study.

Interested in continuing his work, Dr. Beaumont diligently tracked St. Martin down and convinced him to let him continue. Dr. Beaumont extracted samples of gastric secretions in an attempt to delineate their contents. He tested these secretions on various bits of food in containers outside of the body. He was surprised to note that the secretions alone broke food down over time. His observations had led to the discovery of gastric acid, and for the first time doctors understood that digestion was not just a mechanical process.

Alex awoke the next morning and drove to the hospital. He noted the anti-intrinsic factor antibody level he had ordered the day before for Mr. Martin had come back markedly elevated. The esophagogastroduodenoscopy showed findings consistent with atrophic gastritis and a small area concerning for cancer. The area was biopsied, and pathology revealed gastric adenocarcinoma limited to the gastric submucosa.

Alex's attending approached him and asked if he had come up with a unifying diagnosis for Mr. Martin. He responded excitedly that the patient was deficient in gastric acid, the same acid that Dr. William Beaumont had extracted from Alexis St. Martin nearly 200 years ago though a gastrocutaneous fistula. His attending gave him a strange look. Alex started again and explained instead that Mr. Martin had autoimmune atrophic gastritis, which had led to B12 deficiency, iron deficiency, and stage I gastric cancer. His attending nodded in approval and instructed him to start treatment. Alex initiated B12 and iron supplementation and arranged for outpatient oncology consultation. He explained the diagnosis to Mr. Martin and his wife, and they were relieved that the condition was treatable. He also gave them a brief history lesson.