Infected femoral closure device after cardiac catheterization

A patient presented with cellulitis at a vascular access site 10 days after undergoing cardiac catheterization.

The patient

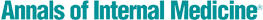

A 61-year-old woman with a history of coronary artery disease, chronic angina, obesity, and poorly controlled insulin-dependent type 2 diabetes presented with progressively worsening nausea and vomiting as well as right inguinal pain and swelling with purulent discharge. Ten days earlier, she had undergone cardiac catheterization for ST-segment elevated myocardial infarction. At that time, the right femoral artery was utilized for angiography and was subsequently closed with a 6-French vascular closure device (VCD). On this presentation, physical exam revealed a foul-smelling, diffusely tender, indurated, and erythematous right lower quadrant abdomen and inguinal region. There was a ruptured bulla with bloody discharge surrounding the previous vascular access site (Figure 1).

Labs found leukocytosis of 23.67 K/μL (reference range, 4.80 to 10.80 K/μL) and elevated C-reactive protein level at 35.5 mg/dL (reference range, <0.9 mg/dL). She was also noted to have a hemoglobin A1c level of 11.9% (reference range, 4.5% to 6.2%). A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast showed subcutaneous edema consistent with cellulitis and phlegmon formation (Figure 2). Vascular surgery was consulted, and the patient was taken emergently for incision, drainage, and exploration of the wound. Operative findings included purulent fluid, necrotic tissue, and a single polypropylene suture on the anterior wall of the femoral artery. Femoral arteriotomy was performed proximal and distal to the suture. The suture was then removed, and the femoral artery was closed with a non-absorbable suture. A sartorius muscle flap technique was used to protect the vascular structures. Two-thirds of the wound was left open, and a wound vacuum-assisted closure was placed. Wound culture results showed Streptococcus agalactiae and Prevotella bivia. The patient was placed on a continuous cefazolin infusion for six weeks via a peripherally inserted central catheter.

The diagnosis

The diagnosis is infection associated with a VCD. Most VCDs can be broadly categorized as active or passive. Active devices use sutures or clips to physically approximate an arteriotomy site, while passive devices form a plug to seal the arteriotomy site without physically closing it, using collagen or some other type of sealant or gel. The advantage of VCDs over the traditional method of manual compression is increased patient comfort and satisfaction, as well as decreased time to hemostasis and ambulation. Research on bleeding and ischemic complications at 30 days in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention by the transfemoral approach found VCDs to be noninferior in comparison to manual compression, even in patients on long-term oral anticoagulation. However, infectious complications tend to be more frequent. The mechanism of infection is likely due to hematoma formation and foreign material (e.g., suture) serving as nidus of infection. Commonly identified comorbidities are diabetes, obesity, and placement of VCD in the last 6 months. The most commonly involved organism is Staphylococcus aureus, seen in up to 75% of cases.

Although these infections can be difficult to distinguish from a typical complicated cellulitis/abscess, it is crucial to do so because in some cases vascular involvement rapidly progresses to sepsis and endarteritis and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Clinical suspicion should be high in patients with local signs of inflammation, leukocytosis, and/or fever one to two weeks after device placement. For all patients with suspected VCD-associated infection, two sets of blood cultures should be drawn before initiating empiric antibiotic therapy covering for methicillin-resistant S. aureus. The depth of the infection and structures involved should also be evaluated by soft-tissue ultrasound or CT scan with IV contrast. Treatment should entail at least four to six weeks of culture-directed systemic antibiotic therapy. If the infection has progressed to the point of vascular involvement, further interventions beyond debridement may be required. Vascular surgery should be consulted for potential removal of the VCD and repair with vascular graft, bypass of affected femoral segment, and/or soft-tissue coverage of exposed arterial repair.

Pearls

- Differentiation of VCD infection from typical complicated cellulitis is crucial because vascular involvement can rapidly progress to sepsis and endarteritis and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality.

- Risk factors for VCD infection are diabetes, obesity, and placement of VCD within six months.