Learn the art of sickle cell treatment

An expert offered a housestaff-friendly, nursing-friendly, patient-friendly approach to vaso-occlusive crises in the hospital.

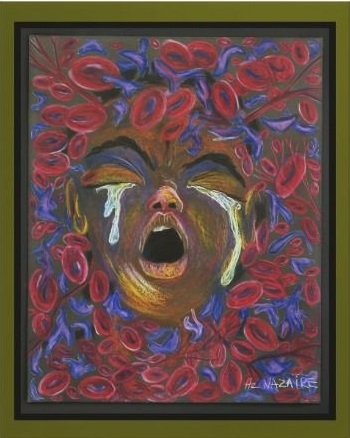

To convey the pain and frustration that affect many inpatients with sickle cell disease, Michael R. DeBaun, MD, MPH, turned to art.

He showed Internal Medicine Meeting 2022 attendees a painting by a young artist who had sickle cell disease and told the hospital anecdote that inspired it. “He said, ‘My pain is 10.’ And the nurse said, ‘You know you don't need medication.’ And he said, ‘What level of 10 do I need to give you before you give me the medication?’”

The exchange that led to the painting of “Ten Redefined” is a disturbingly common occurrence, according to Dr. DeBaun, a professor of pediatrics and medicine and director of the Vanderbilt-Meharry Center for Excellence in Sickle Cell Disease in Nashville, Tenn.

“The interaction on the floor between the nurses who are extremely busy and a patient who asks for PRN pain medication—that is a catastrophe for adults and children with sickle cell disease,” he said.

Busyness is only part of the problem. There's also racial bias, Dr. DeBaun said, citing a 2001 study published by Applied Nursing Research. “Out of the 77 nurses who responded, 63% believed that a drug addiction frequently develops in the treatment of sickle pain episodes; 32% thought most patients with sickle cell disease were drug addicts and this was a barrier to their treatment.”

Evidence disproves these beliefs. “The literature is replete in demonstrating that the rate of opioid misuse in adults with sickle cell disease is no higher than in the general population,” he said.

Given that pain is subjective, variable, and unpredictable, there's one reliable method to assess it in vaso-occlusive episodes, according to Dr. DeBaun. “It's trust.”

That said, as care of adults with sickle cell disease continues to shift from hematologists providing inpatient care to hospitalists, several other steps can also be taken to improve inpatient sickle cell pain treatment, he added. “This is our housestaff-friendly, nursing-friendly, patient-friendly approach, which I think is very important.”

The process begins by distinguishing the type of pain. “Oftentimes, there's an assumption that the pain that the individual has is sickle cell pain, when in fact it's not,” said Dr. DeBaun. “The basketball player that has been playing eight hours of basketball in a hot gym coming to the emergency room and complaining of lower back pain—that's not his sickle cell disease, OK? And yet he's admitted to the hospital for sickle cell pain.”

Sickle cell disease can be associated with both acute, intermittent pain due to vaso-occlusion and with chronic pain from factors such as depression, neuronal sensitization, or avascular necrosis. Patients must be asked questions to help identify the type of pain because it will determine management.

“Listen to their symptoms in a way that helps them distinguish their acute sickle cell pain from chronic pain,” Dr. DeBaun said.

If patients believe their pain to be caused by an acute sickle cell episode, they should already have implemented their home treatment plan, which typically starts with nonmedicinal approaches such as a heating pad, warm bath, message therapy, acetaminophen, or an NSAID before escalating to oxycodone and, if the pain continues, seeking care from a physician or the hospital.

“Every patient with sickle cell disease should have a pain action plan—really no different than an asthma action plan. This is so that the patient is empowered to manage their disease. If they come to the emergency room not [having started] their pain action plan, then we will actually initiate their pain action plan accordingly, as opposed to just immediately putting in an IV and giving intravenous morphine and fluids,” he said..

When the severity of a pain episode requires IV morphine, Dr. DeBaun's treatment approach to sickle cell may differ from others (he noted that it is outlined in the UpToDate section on sickle cell disease, of which he is the editor).

“We don't use PRN medication for any of our children or adults admitted to the hospital, regardless of the service,” he said. “In some hospital settings, it can be up to an hour [from when a patient requests] PRN medication prior to that patient actually receiving that.”

He recommends instead an infusion that is continuous or scheduled every two hours. “That will be the preferred interval. The idea that you'd give morphine every four hours is outside of the boundaries of an effective morphine dose,” he said, noting that morphine's effects might last three hours in some patients, but two hours is more typical.

“I can tell you that in the hematology field … everybody has an opinion about what is the best way to manage patients in this pain. Our preference is rely on the pharmacology of the drug to give them enough of a continuous medication to keep them comfortable, with the goal of putting them in the therapeutic window,” Dr. DeBaun explained. He elaborated that the window is the dose range of a drug that provides effective therapy with minimal adverse effects.

The alternative, which some employ, is to provide a lower continuous dose and use patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) to relieve the pain. “The challenge when this strategy is taken is the patient must wake up in the middle of the night to receive their PCA dose because the morphine level has dropped to the point that they are having pain. When you talk to patients, and you say, ‘Would you like to wake up in the middle of the night to receive your PCA dose to put you back in the therapeutic window?’, the answer is no,” he said.

Even with Dr. DeBaun's system, patients will likely have breakthrough pain, for example, when they need to move to the bathroom or for scans or therapies. He treats that with PCA, but it comprises a relatively low percentage of the overall pain medication.

“A reason we use our strategy as a nurse- and housestaff-safe approach is the PCA is one-sixth of the hourly infusion, with 20-minute lockout for each dose. This approach allows the patient to be safely managed in the hospital, while decreasing the likelihood of respiratory depression because we've only increased the dose by a maximum of 50% within an hour, and the dose must be self-administered,” he said.

If patients are using all of their PCA doses for multiple hours, it's time to consider increasing their continuous infusion, he noted. “This has to be individualized, which is probably one of the challenges,” he said.

Another obstacle may be hospital protocol, as he found on a recent visit to another facility. “Hospitalists or specialists can't start PCAs with continuous infusion without an anesthesiologist, despite the fact that they have board-certified internists, board-certified emergency department physicians,” Dr. DeBaun said.

It doesn't take specialization to provide the supportive therapies that help with sickle cell pain episodes, though. “The most important supportive care measure is the incentive spirometer,” he said. “In the absence of the use of an incentive spirometer, there is a much higher rate of acute chest syndrome, a potentially life-threatening complication.”

Patients should use the incentive spirometer 10 times every two hours, and it takes a team to make this happen, Dr. DeBaun noted. “It really requires partnership between the family, or the individual who has the disease and may be asleep because they're tired, and so the family members and the nurses should remind them of the importance of taking 10 deep breaths every two hours.”

Don't put patients on oxygen by default when their oxygen saturation is normal, but do keep an eye on their saturation. “We use the patient's baseline oxygen saturation as a monitor for acute respiratory illness, and if you put them on a liter or two liters of oxygen, there's no evidence that there's any benefit, and yet, you may mask a patient dropping O2 saturation from 97% to 93%, an alarming decreasing in their saturation and cause for additional evaluation,” he said.

Do encourage patients to get out of bed, once their pain is controlled, and learn the do's and don'ts of supportive medications. Constipation can be treated with a stimulant or senna, but not osmotics. “This is probably one of the biggest challenges is we don't use our osmotic agents when we give opioids. It sounds obvious, but it turns out that many of the patients are put on osmotic agents for constipation while being treated with opioids—a strategy not likely to be effective.”

Finally, for pruritis associated with morphine, loratadine and cetirizine (second-generation histamine-1 antagonists) are preferable, and a naloxone drip is OK, but IV or oral diphenhydramine is not.

“Benadryl has a set of properties that may alter the seizure threshold, and the last thing you want is an individual with sickle cell disease who has a seizure on the floor. Other side effects include somnolence and hallucinations that may cause a fair number of challenges to manage,” Dr. DeBaun said.