An atypical presentation of microscopic polyangiitis

A patient was admitted after outpatient labs indicated acute worsening of kidney disease and anemia.

The patient

An 81-year-old man with a history of nonischemic cardiomyopathy, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, stage 3 to 4 chronic kidney disease, mitral regurgitation, type 2 diabetes (diet-controlled), and anemia presented to the ED after outpatient labs indicated acute worsening of kidney disease and anemia. Over the previous 1.5 years, his creatinine level had been gradually rising from a baseline of 1.2 mg/dL (reference range, 0.74 to 1.35 mg/dL).

He had been hospitalized for an acute episode of anemia 15 months prior to this admission, suspected to be due to occult gastrointestinal blood loss, but no source was identified. Most recently, he had been hospitalized one month prior for heart failure exacerbation, atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response, and acute kidney injury on chronic kidney disease, with a hemoglobin level of 9 g/dL (reference range, 13.5 to 17.5 g/dL) and a creatinine level of 3.86 mg/dL at discharge.

On admission, aside from chronic shortness of breath, he was otherwise asymptomatic. Vitals and physical exam were unremarkable. His hemoglobin level was 6.7 g/dL, requiring transfusion, and his creatinine level was 5.30 mg/dL. Urinalysis demonstrated proteinuria and hematuria with mixed casts and no dysmorphic red blood cells. Anemia workup was remarkable for mild iron deficiency anemia, appropriate reticulocyte count, and normal erythropoietin level.

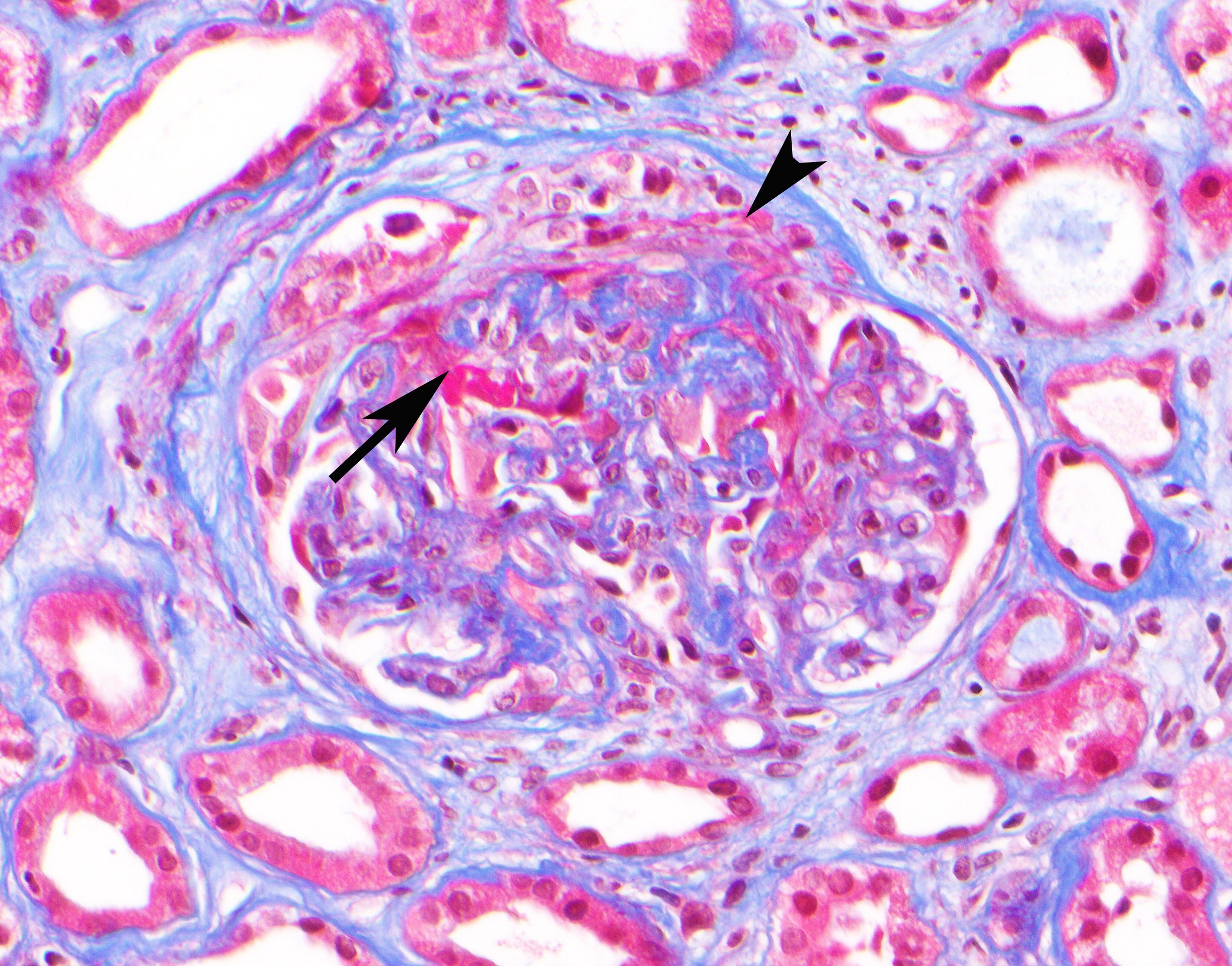

Glomerulonephritis workup was remarkable for positive perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (pANCA) and antimyeloperoxidase (anti-MPO) antibody. He underwent kidney biopsy, which revealed pauci-immune necrotizing and crescentic glomerulonephritis consistent with ANCA vasculitis (Figure). He was started on high-dose steroids with taper and rituximab and discharged from the hospital with close nephrology outpatient follow-up. Since discharge, his renal function remains stable and he has not required dialysis.

The diagnosis

The diagnosis is microscopic polyangiitis (MPA). MPA is one of the ANCA-associated vasculitides, a group that also includes granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), renal-limited vasculitis, and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA). MPA typically presents in patients older than 50 years of age and is more prevalent in Asian populations, whereas GPA occurs more commonly in Western populations. The clinical manifestations of MPA and GPA can be quite similar. Over 70% of patients with either condition have constitutional symptoms. The small vessels in almost any organ or tissue can be affected, but the kidneys and the pulmonary system are most commonly involved. Symptoms range in severity from acute pulmonary-renal syndrome to a more indolent course as seen in this patient. Other manifestations can involve the skin, eyes, and nervous, gastrointestinal, and cardiovascular systems. In addition to renal failure, the anemia, suspected gastrointestinal bleed, and cardiac disease found in this patient may have been driven in part by vasculitis.

While MPA and GPA are similar, some clinical and laboratory findings can help distinguish the two. Ear, nose, and throat involvement is often more common in GPA. Granulomatous inflammation of the upper respiratory tract and lungs is seen in GPA but is typically absent in MPA. GPA primarily has a cytoplasmic staining pattern associated with proteinase 3 autoantibodies, while MPA primarily has a perinuclear staining pattern associated with myeloperoxidase autoantibodies. However, ANCA tests are not diagnostic for MPA. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies are detected in only 50% to 75% of MPA patients, thus a negative ANCA does not exclude the diagnosis. Diagnosis of MPA requires histological confirmation of vasculitis via renal or surgical lung biopsy as the gold standard.

For both GPA and MPA, it is important to initiate therapy immediately, particularly in patients with organ- or life-threatening disease such as active glomerulonephritis, pulmonary hemorrhage, or cerebral vasculitis. In such cases, treatment typically consists of induction therapy with glucocorticoids and either rituximab or cyclophosphamide, followed by maintenance therapy with rituximab. For those with less severe disease, glucocorticoids and methotrexate are a reasonable therapeutic option. Untreated patients have a 90% mortality rate within two years.

Pearls

- MPA and GPA often present very similarly, but MPA is primarily associated with myeloperoxidase autoantibodies while GPA is primarily associated with proteinase 3 autoantibodies. GPA also has a higher probability of ear, nose, and throat involvement and granulomatous inflammation in the respiratory tract.

- For MPA or GPA patients with organ- or life-threatening disease, it is important to immediately start induction therapy with glucocorticoids combined with either rituximab or cyclophosphamide to prevent further organ damage.