Cases from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas

A group of cases involving lytic lesions.

Case 1: Acute lymphoblastic leukemia causing lytic lesions

The patient

A 40-year-old man with a history of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) presented to the ED after outpatient workup for chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy demonstrated hypercalcemia and acute kidney injury (AKI). He had a calcium level of 15 mg/dL (reference range, 8.5 to 10.2 mg/dL) and a creatinine level of 2.93 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6 to 1.2 mg/dL). His estimated glomerular filtration rate was within normal limits, and his vitals and physical exam were also normal. He reported diffuse bone pain. Repeat laboratory tests conducted in the ED the same day showed a calcium level of 14.1 mg/dL and a creatinine level of 2.93 mg/dL; other labs were normal.

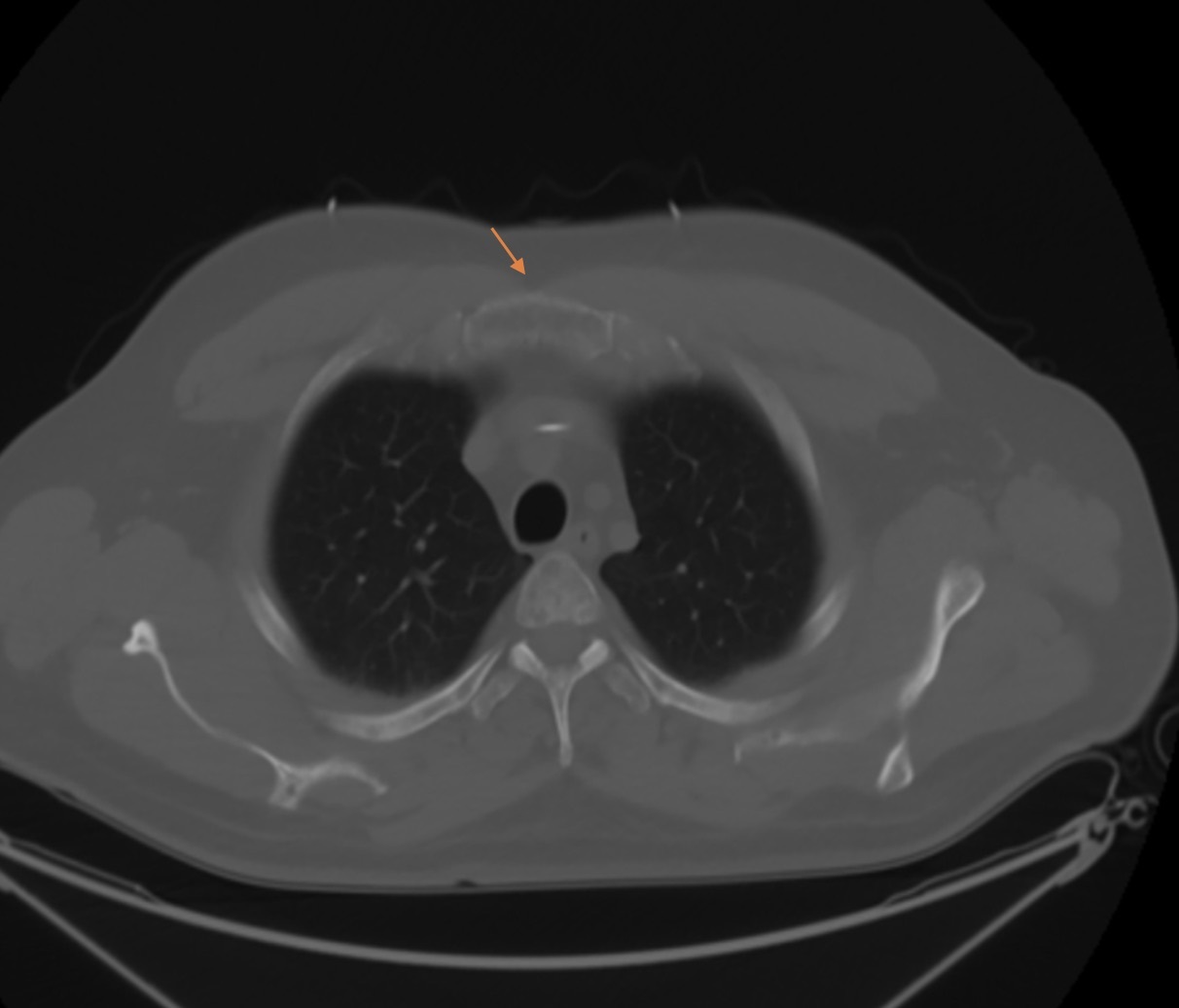

The patient was started on an IV of normal saline at 100 mL/h, and a dose of IV pamidronate was administered. A CT scan revealed lytic bone lesions throughout the axial skeleton (Figure 1). Given his pain, hypercalcemia, and AKI, his lytic bone lesions were concerning for multiple myeloma. A biopsy of the lesions came back negative for multiple myeloma but revealed ALL in the lytic areas. With IV fluids, the patient's creatinine and calcium levels improved to 0.79 mg/dL and 8.8 mg/dL, respectively. The patient was discharged to follow-up with his oncologist. He eventually underwent an allogenic bone marrow transplant and has since been in remission.

The diagnosis

The diagosis is ALL with lytic bone lesions. Lytic lesions occur when bone breakdown occurs faster than bone formation. They have a broad differential, which can be summarized by the pneumonic FOG MACHINES: Fibrous dysplasia or fibrous cortical defect, Osteoblastoma, Giant cell tumor or geode, Metastasis(es)/myeloma, Aneurysmal bone cyst, Chondroblastoma or chondromyxoid fibroma, Hyperparathyroidism (brown tumor), Infection (osteomyelitis) or Infarction (bone infarction), Nonossifying fibroma, Enchondroma or Eosinophilic granuloma, Simple (unicameral) bone cyst.

Malignancies account for 20.7% of lytic lesion findings. When malignancy is suspected or high on the differential, a full cancer workup should be initiated. Blood and urine testing, including erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP), and urine protein electrophoresis (UPEP), should be performed when the suspicion for multiple myeloma is high. If this testing suggests malignancy, imaging is appropriate. CT scans are generally more useful in the setting of malignancy, while MRIs are better for soft-tissue findings. Technetium bone scans can help determine bone remodeling activity levels, which are useful to make a definitive diagnosis. Image-guided biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosing multiple myeloma.

ALL is the most common blood cancer in children but can be seen in adults as well. Patients often present with pain in their bones due to the expansion of the leukemia into the bone marrow itself. However, these lesions are rarely lytic in nature. Lytic lesions are seen in 13.1% of pediatric ALL patients; incidence in adults is less certain. Lesions should be biopsied and worked up for myeloma. After the diagnosis of ALL is confirmed, patients should be tested for the presence of the Philadelphia chromosome, which can be treated with a BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitor. If the malignancy lacks this chromosome, treatment with chemotherapy should be started. If it is refractory, options can include CAR-T therapy or bone marrow transplant.

Pearls

- Malignancies account for 20.7% of lytic lesion findings.

- Blood and urine testing, including ESR, CRP, SPEP, and UPEP, should be performed when suspicion for multiple myeloma is high.

Case 2: Histoplasmosis causing lytic lesions

The patient

A 46-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes and a recently repaired left inguinal hernia presented to the ED with left groin pain for four days and progressively worsening diffuse pain in his chest and proximal and distal muscles, as well as fatigue and weakness for two months. He had been started on insulin three weeks prior for his diabetes and thought that was the reason for his newfound weakness. His vitals were within normal limits and his overall exam was normal apart from diffuse weakness. Labs were significant for a blood glucose level of 389 mg/dL (reference range, 70 to 110 mg/dL).

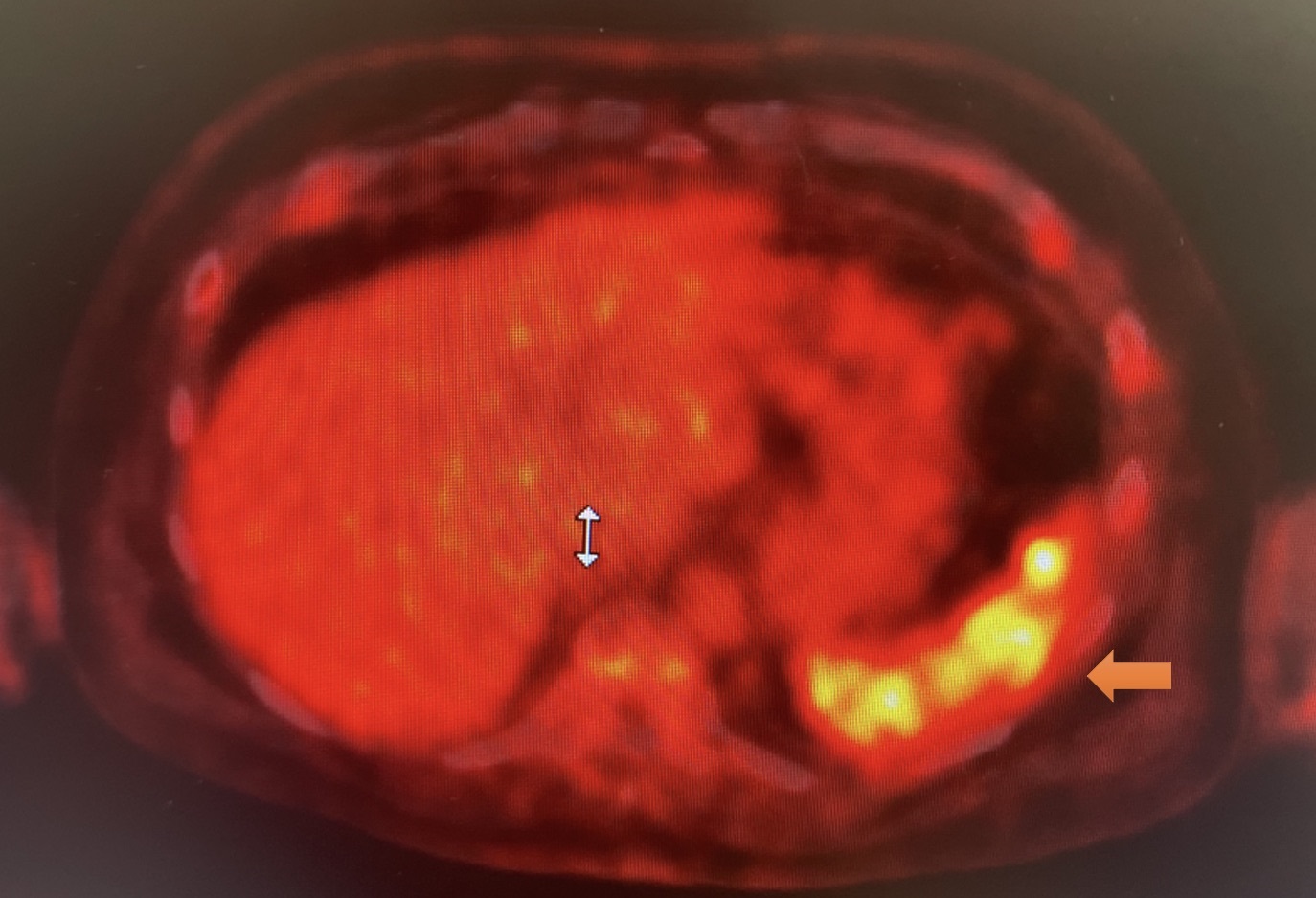

The patient said he had been told he had elevated creatinine and calcium levels at an outpatient appointment earlier that day. A CT of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated multiple lytic lesions in the appendicular and axial skeleton, as did a PET scan (Figure 2). A multiple myeloma workup was initiated. SPEP and UPEP were negative, and a bone marrow biopsy revealed histoplasmosis with necrotizing granulomatous inflammation. After his AKI improved with IV fluid hydration and his creatinine level returned to the baseline value of 0.9 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6 to 1.2 mg/dL), the patient was discharged to follow-up with infectious disease.

The diagnosis

The diagnosis is histoplasmosis with lytic bone lesions. Disseminated histoplasmosis presenting with lytic bone lesions is rare; 26% of cases of disseminated disease are found to have bone lesions, with the African strain Histoplasma duboisii being the most common cause. Histoplasmosis can be classified as acute pulmonary, chronic pulmonary, or progressive disseminated disease. Acute disease may be asymptomatic and may only be found on imaging, or it may present with mild flu-like symptoms. Chronic disease can present with cavitary lesions, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is a major risk factor. Disseminated disease is usually a result of low-grade persistent infection spreading insidiously in the body. This low-grade infection can persist for weeks to months, or, reportedly in some cases, up to two decades.

Disseminated disease can present with a wide range of symptoms and is defined by extrapulmonary disease with positive blood or urine cultures. Slow dissemination results from impaired immune response, often due to a chronic disease such as diabetes. When seen in the bones, infections are usually present in the skull or long bones of the body.

Treatment for severe disease requiring hospitalization is amphotericin B for one to two weeks. The liposomal formulation is preferred to the deoxycholate one due to less nephrotoxicity (15% vs. 33%) and improved clinical success (88% vs. 64%). Patients should then transition to itraconazole for at least a year. For mild to moderate disease, itraconazole therapy alone is indicated. Monitoring of serum drug levels is required, with itraconazole levels checked at two weeks to ensure steady-state levels.

Histoplasma antigen levels in the urine and serum should be checked monthly to ensure decreasing levels while on therapy and should be monitored for an additional two years after therapy conclusion.

Pearls

- Histoplasmosis can cause lytic lesions, seen in 26% of disseminated cases.

- The liposomal formulation of amphotericin B has been shown to decrease nephrotoxicity and improve treatment success compared to the deoxycholate version.

Case 3: Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter infection causing lytic lesions

The patient

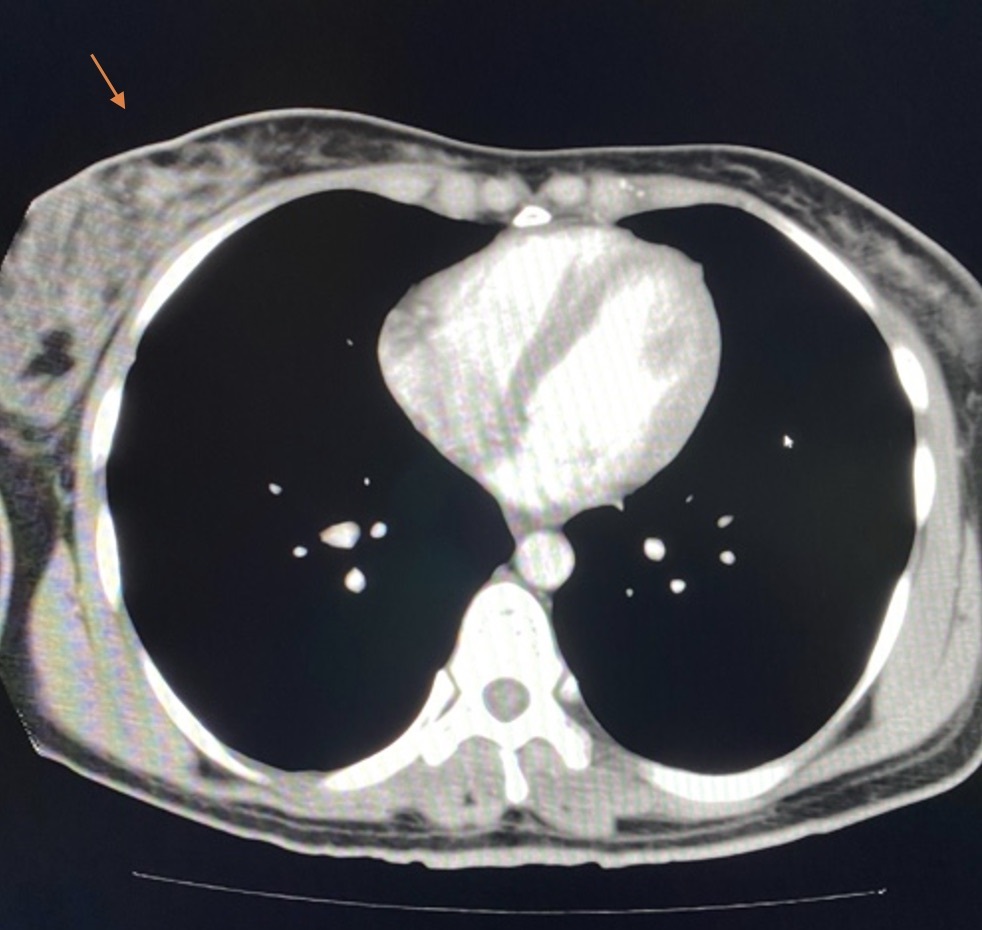

A 62-year-old woman with a history of stage 3A chronic kidney disease, type 2 diabetes, hypothyroidism, and hypertension had been discharged to a skilled nursing facility after treatment at another medical institution for pneumonia. She presented to our ED three weeks later with continued shortness of breath and a productive cough. Initial examination was significant for coarse breath sounds in the right lower base of the lungs and was otherwise unremarkable.

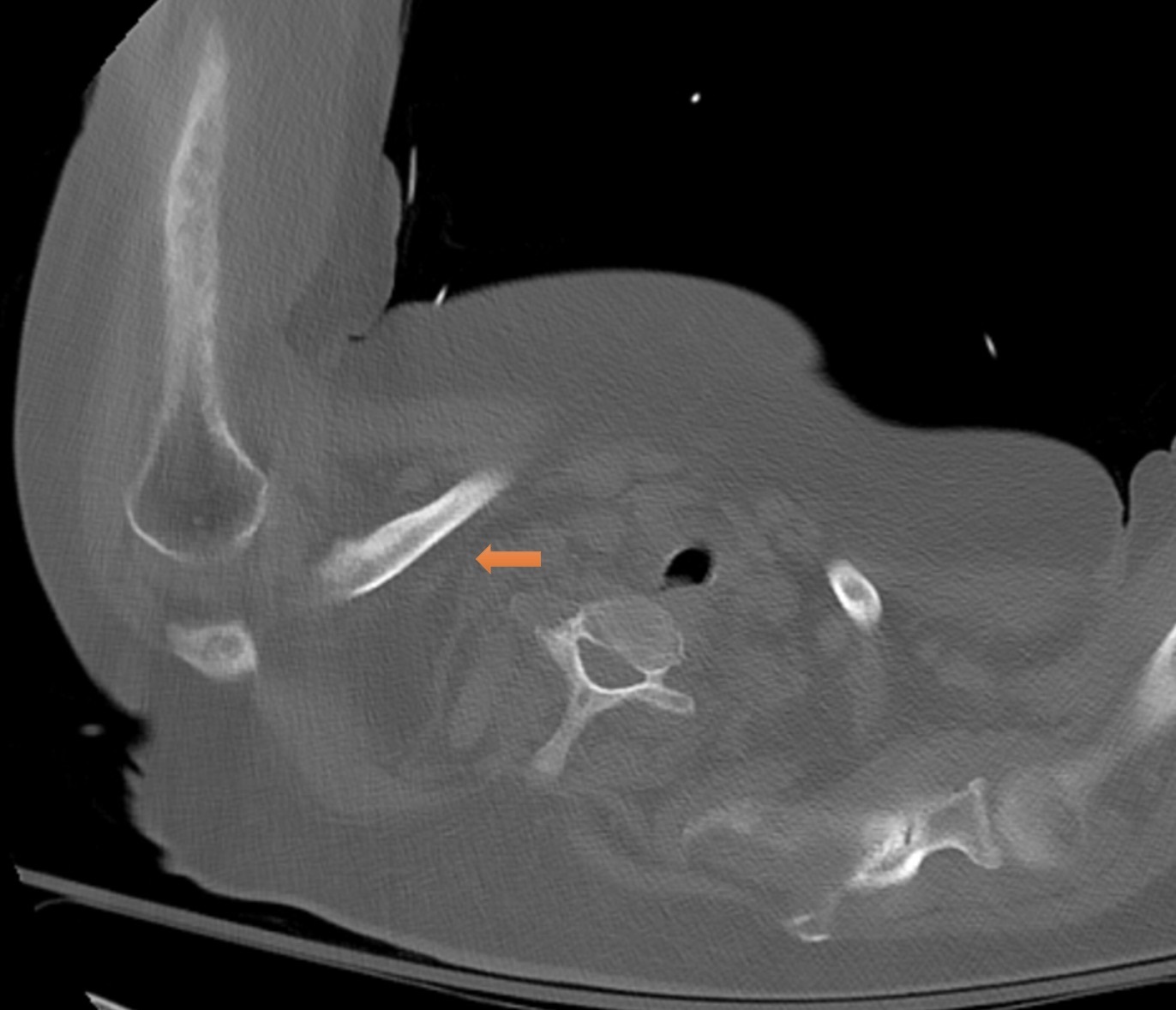

Chest X-ray showed a large pleural effusion (Figure 3). A CT scan revealed a 6-mm × 6-mm right-sided pulmonary nodule, as well as lytic lesions in the right humerus and right clavicular head (Figure 4). Labs were significant for a corrected calcium level of 9.4 mg/dL (reference range, 8.5 to 10.2 mg/dL) and a creatinine level of 1.55 mg/dL, increased from a baseline of 1.00 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6 to 1.2 mg/dL). SPEP and UPEP were negative. A bone scan revealed that the lytic lesions on the CT scan had occurred after a fracture.

With IV fluids, the patient's creatinine level improved to her baseline. Further testing, including a renal ultrasound, parathyroid hormone, and 25-hydroxyvitamin D level, indicated that chronic kidney disease had caused secondary hyperparathyroidism. The pulmonary nodule seen on CT scan was biopsied and was found to be an abscess due to multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter, which was successfully treated with a seven-day course of eravacycline for pulmonary infection. The PET scan found that the lytic lesion was not infectious and did not require therapy.

The diagnosis

The diagnosis is multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter infection with lytic bone lesions. It is estimated that 79.3% of lytic lesion cases are benign. Infections and healing fractures are two benign processes that commonly cause lytic lesions. This patient presented with two notable findings: lytic lesions on the humerus and the clavicle and a biopsy-proven multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter nodule.

Acinetobacter is a commonly resistant organism, with 76% to 90% of isolates being multidrug-resistant. It is a non-motile gram-negative aerobic coccobacilli, responsible for a significant portion of nosocomial infections. It has been known to cause osteomyelitis in rare circumstances. Chronic osteomyelitis, when untreated, may cause lytic bone changes from the breakdown of the bone in response to the infection. These infections are often seen in hospital settings from skin breaks seeding the underlying tissue and the bone itself. Bone scans use the element technetium to determine bone remodeling activity levels and are useful to make a definitive diagnosis.

Acinetobacter has a high mortality rate, between 35% and 70% in ventilator-associated pneumonia. It is part of the ESCAPE class of organisms common to health-care associated infections, which also includes Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Clostridioides difficile, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacteriaceae. An organism is defined as multidrug-resistant if it is not susceptible to an agent in three or more antibiotic classes. First-line therapy for Acinetobacter infection is a broad-spectrum cephalosporin, such as ceftazidime or cefepime, a beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor, or a carbapenem. When resistance is seen, polymyxins are the main therapeutic option. Infection of the bone is considered a marker of moderate to severe infection.

Pearls

- Infections can present as lytic lesions when the infection is in the bone itself, with an estimated 79.3% of lytic bone lesions due to nonmalignant causes.

- Acinetobacter is a major cause of multidrug-resistant infections in the hospital, and polymyxins are the main therapeutic option.

Case 4: Large-cell lymphoma causing lytic lesion in the proximal humerus

The patient

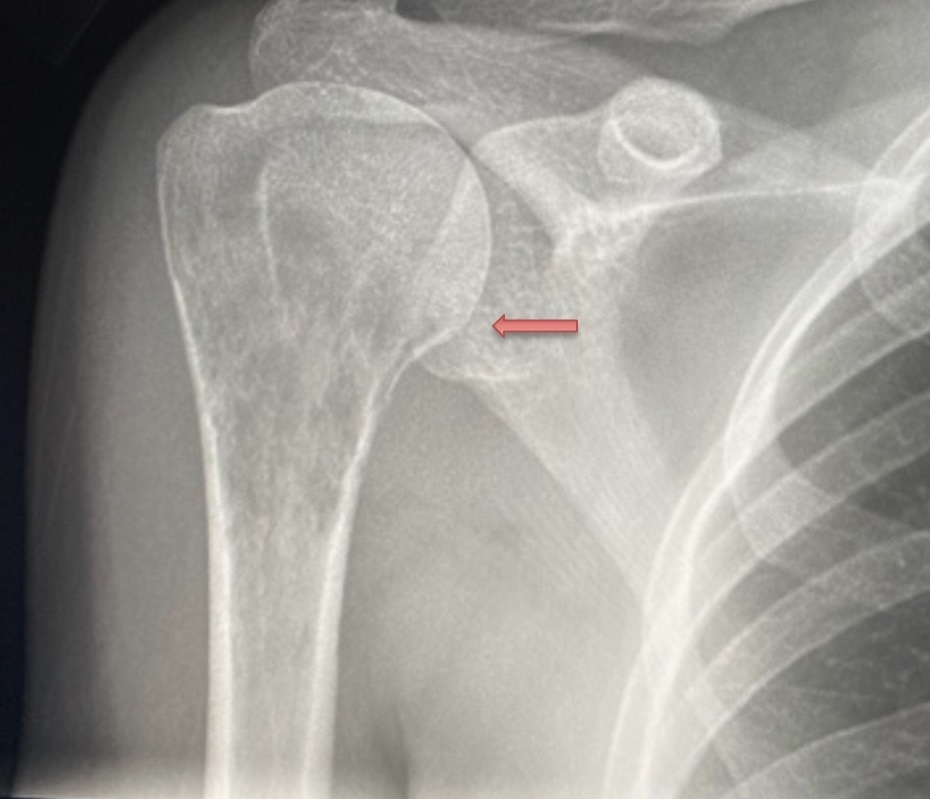

A 30-year-old woman with no significant medical history presented with bilateral breast swelling and right arm pain. Physical examination revealed both breasts fixed to the chest wall with firmness on palpation that extended into the axillae. Inflammatory skin changes were also present, including redness and swelling. An X-ray revealed a lytic lesion in the proximal humerus on the right side (Figure 5). A CT showed a breast mass and lytic lesions on the bones (Figure 6).

A core biopsy of the breast lesion was consistent with a diffuse CD20+ large-cell lymphoma with negative findings for myeloma. The patient was treated with six cycles of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, oncovin, and prednisone (R-CHOP) along with pamidronate over a period of one year and has since been in remission.

The diagnosis

The diagnosis is large-cell lymphoma with a lytic lesion in the proximal humerus. Malignancy is an important differential for lytic lesions. Diffuse large-cell lymphoma is a B-cell cancer and is the most common of the non-Hodgkin's lymphoma subtypes, at 25% of all cases. It can develop from a transformation of another malignancy, in particular the Richter transformation of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Diagnosis is made based on tissue biopsy. Excisional lymph node biopsy is recommended. However, the diagnosis can also be made based on pleural fluid and splenic tissue in patients without lymphadenopathy. Immunophenotyping and histology showing CD20 and CD79a is diagnostic. Clinically, patients present with rapidly enlarging lymph nodes or other mass with B symptoms, including weight loss, fevers, chills or night sweats.

Bone lesions in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma are rare, representing less than 1% of all extranodal findings. However, 70% to 80% of bone lesions occur in patients with large-cell lymphoma, and they are more common in male patients, at a rate of 2:1. In one case series, they were seen 83% of the time in the axial skeleton. Treatment with R-CHOP results in high cure rates, especially when the lesions are found exclusively in the bone, not the lymph nodes, with five-year survival of 84%.

Pearls

- Malignancies such as lymphoma and leukemia can cause lytic lesions to form.

- Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is the most common type of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, at 25% of all cases.

Case 5: Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma causing lytic lesions

The patient

A 45-year-old woman with a history of hypertension presented to the ED with shortness of breath for two weeks. She had no sick contacts but was involved in a bicycle accident a week prior where she was hit on her chest wall by an oncoming bicycle. She had been managing her symptoms with over-the-counter pain medications. Vitals showed mild tachypnea and fever (temperature, 100.3 °F). Physical examination was significant for decreased air entry and was otherwise unremarkable.

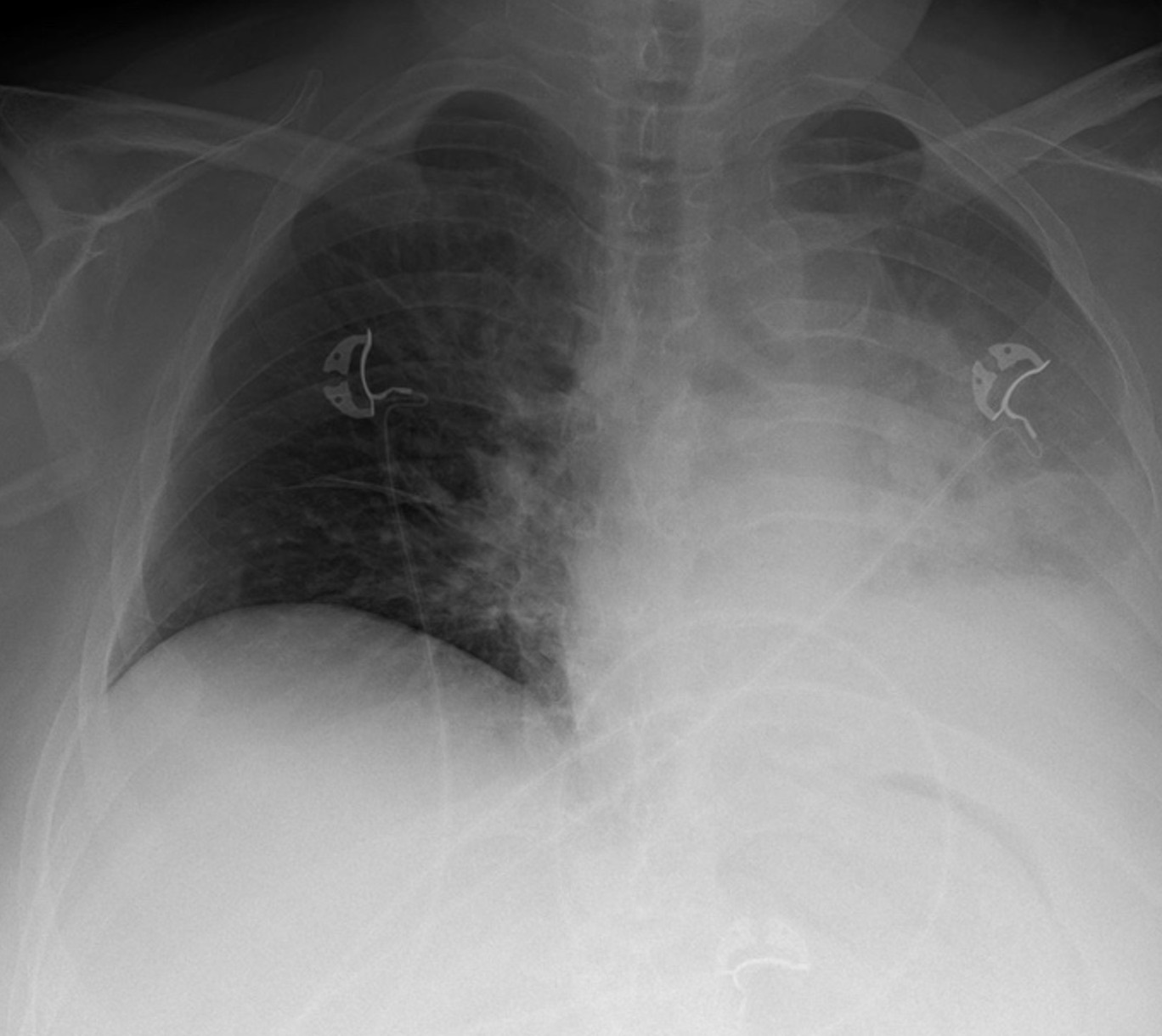

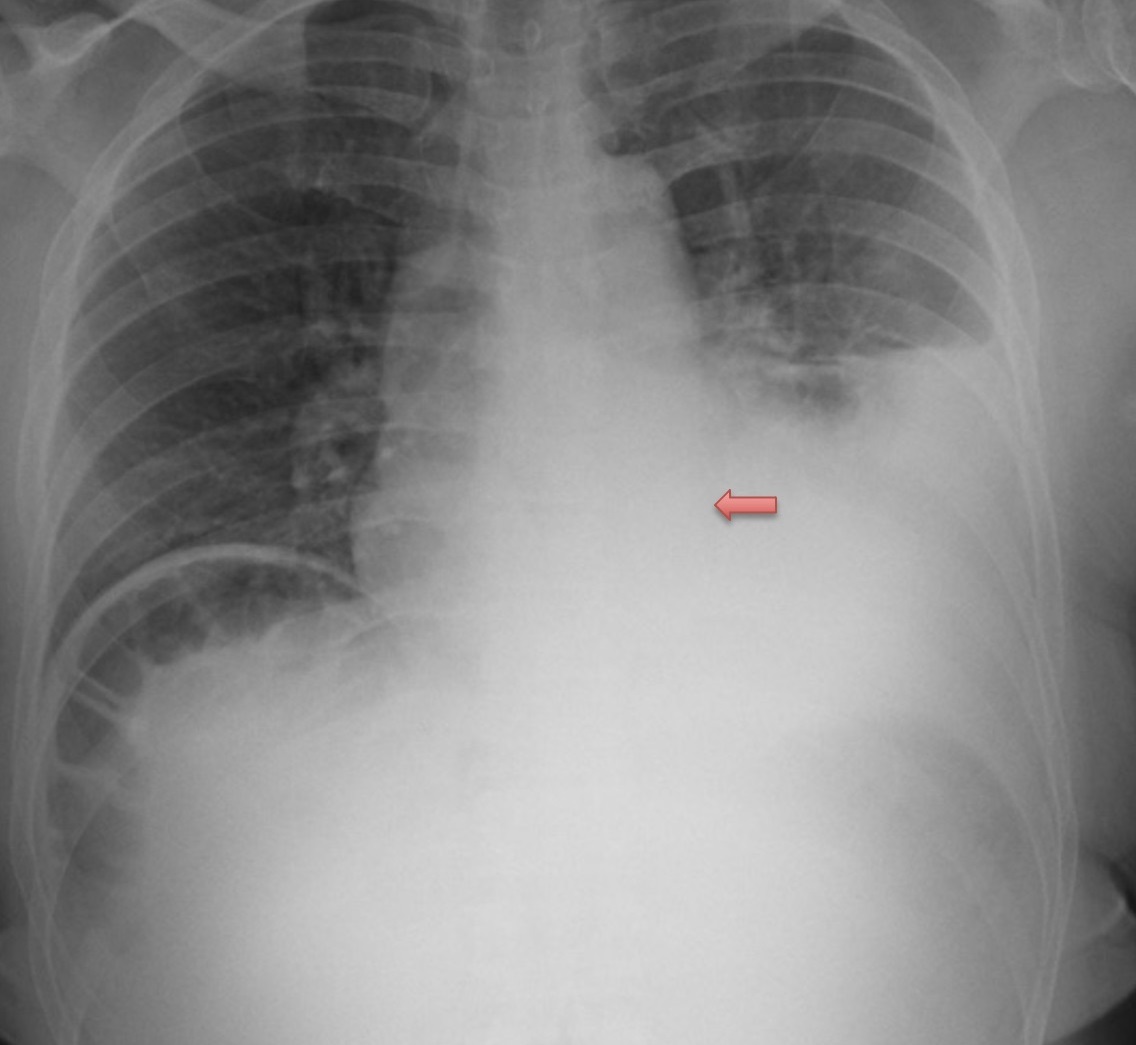

Labs were significant for a white blood cell count of 19.9 × 109 cells/L (reference range, 4.5 to 10 × 109 cells/L), a hemoglobin level of 7.6 g/dL (reference range, 12.1 to 15.1 g/dL), and a mean corpuscular volume of 77.6 fL (reference range, 80 to 100 fL). A chest X-ray revealed a large pleural effusion and a paraspinous mass (Figure 7).

A CT angiogram of the chest showed an aggressive mass lesion at the left lateral and posterior paraspinal space, with osseous lytic lesions in the eighth thoracic vertebral body and in the eighth and ninth right ribs (Figure 8). Biopsy of the paraspinous mass revealed a CD30+ anaplastic large-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. The patient was treated with brentuximab vedotin; doxorubicin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine; and zoledronic acid. She went into remission and subsequently had a stem-cell transplant.

The diagnosis

The diagnosis is non-Hodgkin's lymphoma with lytic bone lesions. This patient had a T-cell proliferative non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, which is much rarer than diffuse large-cell lymphoma and is only found in 15% of cases. Biopsy is the diagnostic gold standard, with genetic testing to further subtype the disease. Skin manifestations in the form of small red nodules are the most common symptoms. It is rare to see bone metastases, but in some cases lymph node metastases can occur. Bone lesions are rare, seen in less than 1% of all non-Hodgkin's lymphoma patients, and are commonly seen in the long bones. Their development could be mediated by factors produced by the tumor cells, including interleukin 1, calcitriol, and PTHrP, which can induce bone turnover and osteoclast activation. These same factors can induce hypercalcemia in up to 30% of patients. Soft-tissue masses and swelling can be present as a result of the disease and are important prognostic indicators; an ultrasound or MRI should be used to evaluate their size. Symptoms can vary from none to compression from the mass itself. A biopsy is required to confirm the diagnosis.

Up to 50% of patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma present with extranodal symptoms. Bone findings indicate aggressive disease. Treatment for non-Hodgkin's disease with chemoradiation with doxorubicin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine followed by stem-cell transplant yields a good prognosis, with five-year survival greater than 90%. The prognosis with T-cell etiologies is lower. ALK positivity has a five-year survival rate of 80%, compared to 48% when negative. Aggressive disease is seen in patients who present when older than age of 60 years or with bone lesions in multiple locations.

Pearls

- Anaplastic large-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma develops from T-cell precursors.

- Bone metastasis in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma is a rare finding, seen in less than 1% of cases; prognosis is worse when seen in multiple locations.