Cases from Main Line Health Lankenau Medical Center

Methemoglobinemia, heart failure, pseudogout, and other diagnoses.

Case 1: Methemoglobinemia due to xylocaine anesthetic for dental extraction

By Wissam Rahi, MD, ACP Resident/Fellow Member; Lauren Davis, DO, ACP Resident/Fellow Member; Amrutha Mittapalli, MD, ACP Resident/Fellow Member; and Raya Terry, MD, FACP

The patient

A 68-year-old woman with hypothyroidism, prior ischemic stroke due to right carotid artery stenosis, and liver cirrhosis without ascites due to untreated hepatitis C virus presented to the ED for unilateral left mandibular pain of two weeks' duration. On physical exam, poor dentition was seen but no visual abscess. Lung auscultation was notable for rhonchi at the right base of the lung but otherwise clear to auscultation.

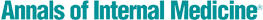

On admission, the patient was afebrile with normal blood pressure and respiration. She was mildly tachycardic with a heart rate of 103 beats/min. Her laboratory results showed normal complete blood count and basic metabolic panel values, including a white blood cell count of 8,000 cells/µL (reference range, 3,800 to 10,500 cells/µL) and a creatinine level of 0.9 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6 to 1.2 mg/dL). A CT of her face and neck showed two premolar abscessed teeth (teeth #12 and #29; Figure 1).

A CT of the chest revealed right lower-lobe ground-glass opacities that were consistent with aspiration pneumonia, prompting the initiation of ampicillin-sulbactam. A fluoroscopy video swallow study showed moderate oral and mild pharyngeal dysphagia. The patient underwent bedside extraction of her abscessed teeth on day 2, with 3.4 mL of local 1% xylocaine anesthetic.

Two hours postprocedure, a rapid response was called because the patient had become unresponsive. Oxygen saturation via pulse oximetry was 60%. An arterial blood gas revealed severe metabolic acidosis with a pH of 6.9 (reference range, 7.35 to 7.45), a lactate level greater than 13 mmol/L (reference range, 0.4 to 1.6 mmol/L), and a partial pressure of oxygen close to the lower limit of normal at 73 mm Hg (reference range, 75 to 100 mm Hg).

The patient was intubated, with a subsequent increase in her partial pressure of oxygen but unchanged oxygen saturation. She soon developed hypotension refractory to multiple vasopressors, with evidence of multiorgan failure and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Laboratory studies showed an international normalized ratio (INR) of 6.8 (reference range, 0.8 to 1.1), a partial thromboplastin time of 138 seconds (reference range, 23 to 35 s), and a fibrinogen level of 105 mg/dL (reference range, >200 mg/dL).

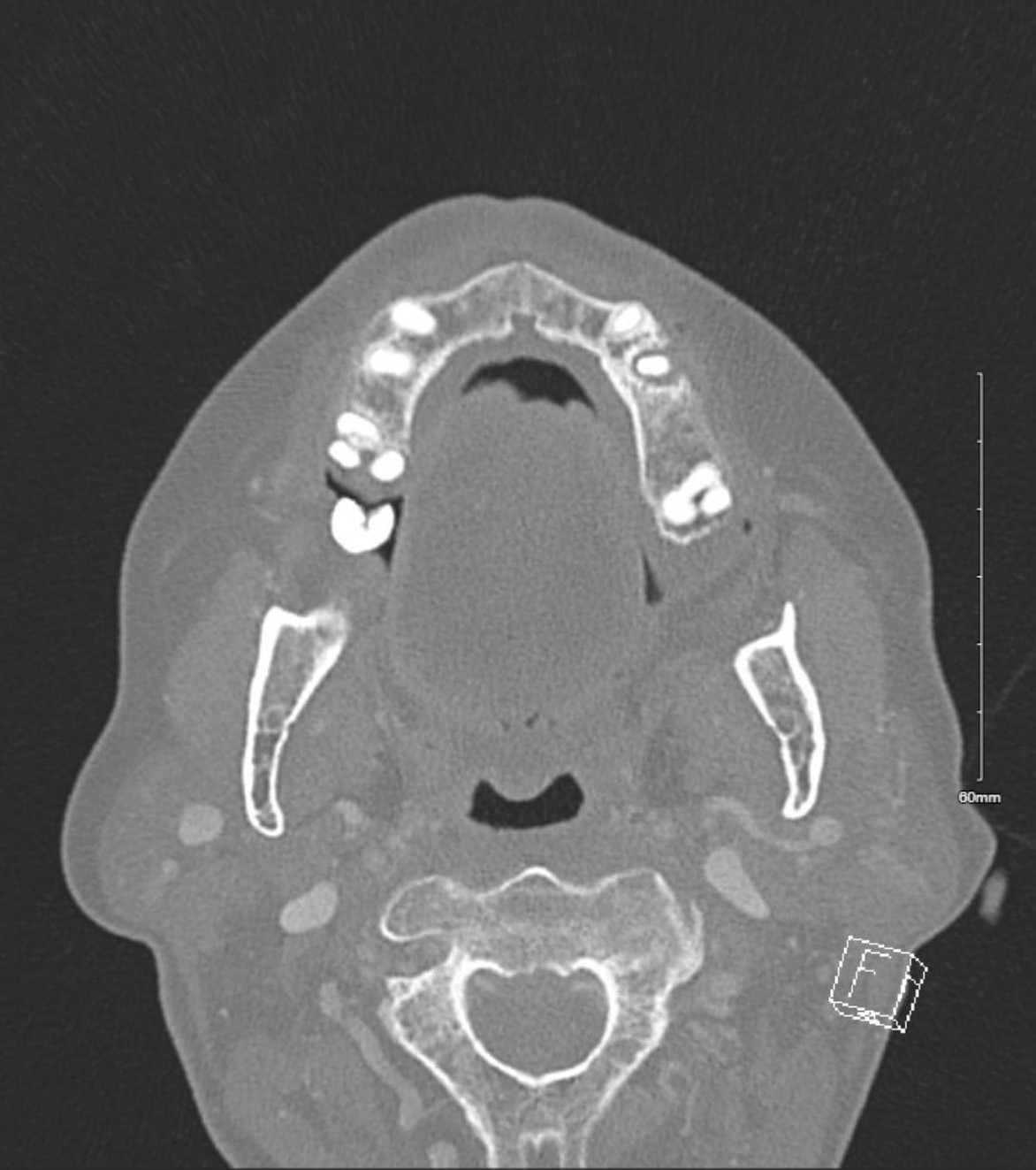

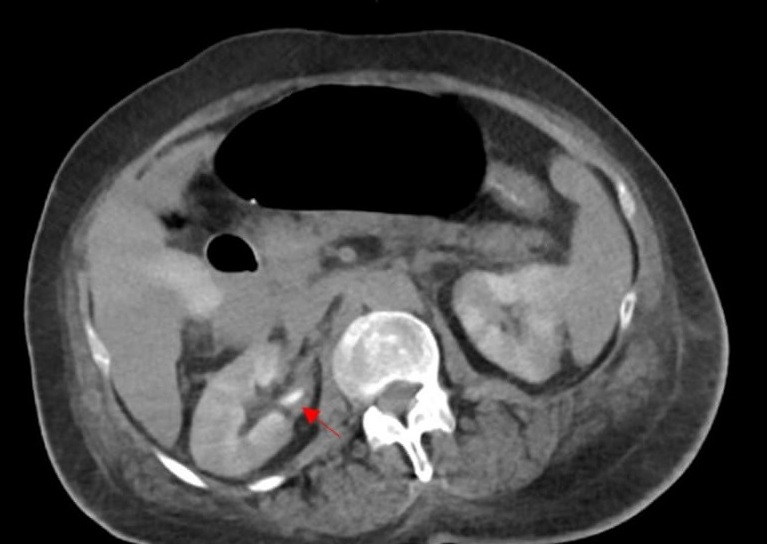

CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed diffuse ischemic injury, mainly in the colon (Figure 2) and kidneys (Figure 3).

Because the patient was experiencing refractory hypoxia with a marked difference between her predicted and actual oxygen saturation after receiving an anesthetic, methemoglobinemia was high on the differential diagnosis. She received an infusion of 1 mg/kg of methylene blue over a period of 20 minutes, with improvement in her oxygen saturation to expected levels after the infusion was completed. However, despite aggressive measures, the patient experienced cardiac arrest and could not be resuscitated.

The diagnosis

The diagnosis is methemoglobinemia. Methemoglobinemia is a condition characterized by conversion of some or all of the iron in hemoglobin to the oxidized ferric state from the reduced ferrous state. This causes a reduction in hemoglobin's oxygen-carrying capacity because iron in the ferric state cannot bind oxygen. Exposure to substances that directly or indirectly cause oxidation of iron can cause the production of oxidized methemoglobin that outpaces the body's capacity to convert it back to reduced hemoglobin, causing functional anemia.

Local anesthetics such as benzocaine, xylocaine, and prilocaine are direct oxidating agents and rarely cause methemoglobinemia. Benzocaine has been shown to cause methemoglobinemia more frequently than the other agents, although still at low rates, with retrospective studies finding incidences of 0.060% and 0.035%. Inpatient status has been associated with higher risk of methemoglobinemia, but the condition has rarely been reported with dental anesthesia.

Risk factors include high doses or prolonged use of local anesthetics, genetic defects in cytochrome b5 reductase or G6PD, and extremes of age. This patient's differential hypoxia raised suspicion for methemoglobinemia, and the diagnosis was further supported by the improvement in oxygen saturation after administration of methylene blue infusion. Methylene blue reduces oxidized methemoglobin to reduced hemoglobin, allowing an increase in the blood's oxygen-carrying capacity.

Given methylene blue's rapid onset of action, prompt recognition and treatment of methemoglobinemia can reverse symptoms and prevent morbidity and mortality. Typically, symptoms of methemoglobinemia start to develop when methemoglobin levels are above 5% of total hemoglobin. The mortality risk from methemoglobinemia increases with higher methemoglobin levels, and if not treated promptly, rates can be as high as 70% when methemoglobin levels exceed 20% or cyanosis, hypoxia, dyspnea, or cardiovascular instability is present.

Methylene blue is generally well tolerated but carries an increased risk of serotonin syndrome when used with serotonergic drugs. It can also precipitate hemolysis in patients with G6PD deficiency. Women of childbearing age should get a pregnancy test before administration, as methylene blue can have teratogenic effects on the fetus, such as neonatal intestinal atresia. However, in cases of hemodynamic instability, this should not delay treatment. Prior to initiation, the level of methemoglobin should be checked because the dose is dependent on the level of methemoglobin in the blood. Other treatments for this condition include vitamin C, hyperbaric oxygen, and blood transfusions.

Pearls

- Methemoglobinemia is marked by refractory hypoxia and elevated methemoglobin levels, often after exposure to an inciting agent.

- Methylene blue remains the first-line treatment for methemoglobinemia, and the dose is dependent on the level of methemoglobin in the blood.

Case 2: HIV-associated immune thrombocytopenia

By Amrutha Mittapalli, MD, ACP Resident/Fellow Member; Matthew Sanborn, DO, ACP Resident/Fellow Member; Bernita Vanessa Sidhu, MD, ACP Resident/Fellow Member; and Raya Terry, MD, FACP

The patient

A 31-year-old woman with a history of iron deficiency anemia and untreated HIV infection, complicated by prior pneumocystis pneumonia and cryptococcal meningitis, presented to the ED with a three-week history of headache, weakness, vomiting, odynophagia, and gingival bleeding. On presentation, she was tachycardic, with a heart rate of 130 beats/min, and her physical exam was remarkable for white, curd-like plaques on the tongue, buccal mucosa, and oropharynx that could be scraped off.

Laboratory values revealed severe thrombocytopenia, with a platelet count of 7,000 cells/µL (reference range, 150,000 to 369,000 cells/µL), and iron deficiency anemia, with a hemoglobin level of 5.8 g/dL (reference range, 11.8 to 15.7 g/dL), a serum iron level of 17 µg/dL (reference range, 35 to 150 µg/dL), an iron saturation of 4% (reference range, 15% to 45%), a ferritin level of 27 ng/mL (reference range, 11 to 250 ng/mL), and a reticulocyte count of 1.88% (reference range, 0.6% to 2.80%). Immature platelet fraction was elevated at 21% (reference range, 1.8% to 8.9%), and a peripheral smear showed rare schistocytes.

Coagulation screen, haptoglobin, fibrinogen, lactate dehydrogenase, liver function tests, INR, and bilirubin were all within normal limits. Her CD4 cell count was 11 cells/mm3 (reference range, 443 to 1,705 cells/mm3) and her HIV viral load was 128,000 copies/mL. Lab work from three years prior showed a CD4 cell count of 8 cells/mm3 and an HIV viral load of 205,000 copies/mL. A CT scan of the head showed no evidence of acute intracranial processes.

Given the unclear cause of the patient's severe thrombocytopenia, initial management was supportive with platelet transfusions. The platelet count did not correct appropriately, rising less than the expected 10,000 cells/µL with one unit of random donor platelets, raising suspicion of immune thrombocytopenia. Steroid therapy was initially deferred due to concerns about the risk of untreated opportunistic infections, such as tuberculosis and cryptococcus meningitis, that can be exacerbated by steroids. Fluconazole was started empirically for esophageal candidiasis. After a thorough workup, including lumbar puncture, sputum culture, and silver stain, ruled out meningitis, tuberculosis, and pneumocystis pneumonia, a four-day course of oral dexamethasone, 40 mg, was initiated on hospital day four, resulting in a rapid recovery of platelet counts to 207,000 cells/µL.

The diagnosis

The diagnosis is HIV-associated immune thrombocytopenia (ITP). Thrombocytopenia is seen in up to 40% of patients with advanced HIV (CD4 cell count <200 cells/mm3), due to various causes, including bone marrow suppression, opportunistic infections, and ITP. HIV ITP is characterized by a low platelet count, secondary to immune-mediated destruction of platelets and inefficiencies in platelet production. Although ITP is a diagnosis of exclusion, severe thrombocytopenia, an elevated immature platelet fraction, and refractoriness to platelet transfusions are commonly associated with this condition, occurring at a rate between 6% and 15% of patients with HIV. Higher incidence of HIV ITP can be seen in patients who have co-infection with hepatitis C virus and cirrhosis.

In suspected ITP, corticosteroids are the first-line therapy once other causes of thrombocytopenia—such as infection and thrombotic microangiopathies—are excluded. In immunocompromised patients, steroid initiation should be delayed until active infections are reasonably excluded.

Pearls

- HIV ITP is a diagnosis of exclusion, so other causes of thrombocytopenia must be considered prior to diagnosis and management.

- In immunocompromised patients with suspected ITP and concern for opportunistic infections, corticosteroid therapy may need to be deferred until active infection is ruled out.

Case 3: Diuretic-resistant heart failure

By Bernita Vanessa Sidhu, MD, ACP Resident/Fellow Member; Sebastiano Porcu, MD, ACP Resident/Fellow Member; and Raya Terry, MD, FACP

The patient

A 93-year-old woman with heart failure (New York Heart Association class IV) with preserved ejection fraction (55%), hypertension, hypothyroidism, stage 4 chronic kidney disease (baseline creatinine level, 2.8 mg/dL; reference range, 0.7 to 1.2 mg/dL), and persistent atrial fibrillation on apixaban was readmitted 24 hours after her fourth admission in six months for worsening shortness of breath and lower-extremity edema.

Physical exam was significant for elevated jugular venous distention and bilateral lower-extremity pitting edema to the thigh. Laboratory values were significant for an elevated brain natriuretic peptide level of 252 pg/mL (reference range, <100 pg/mL). Her previous diuresis had been limited due to a progressive decline in renal function (creatinine level, 3.2 mg/dL postdiuresis).

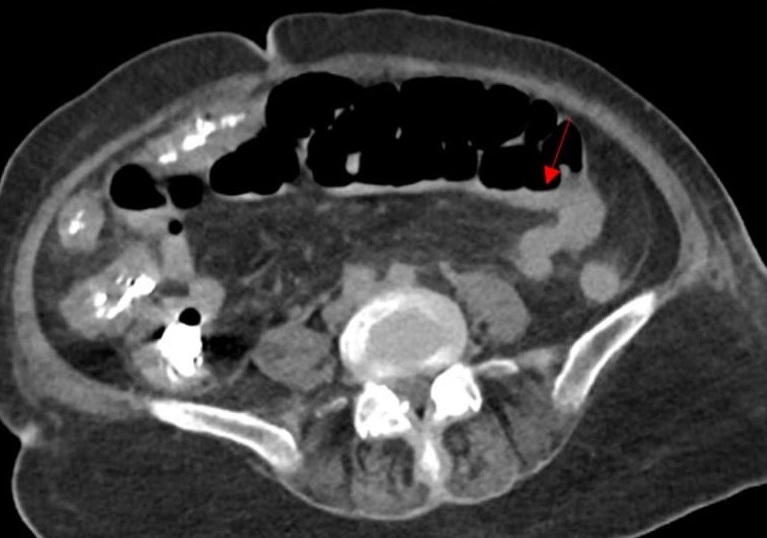

Noncontrast CT of the chest on this admission revealed rapid re-accumulation of the patient's pleural effusions (Figure 4), without evidence of infection or other inciting factors. Therapeutic thoracentesis was performed to address large, bilateral pleural effusions and met Light's criteria for a transudative effusion, with no evidence of cirrhosis or nephrotic syndrome.

Despite the patient's initial desire for life-prolonging care, she declined cardiopulmonary resuscitation, intubation, and hemodialysis for volume removal due to concerns about worsening quality of life. Symptom management became the priority, but aggressive IV diuresis was limited due to leg cramps and progressive renal dysfunction. Therefore, a pleural catheter was placed.

The patient experienced severe pain from the catheter placement and developed a small pneumothorax found to be due to trapped lung. Further catheter placement was considered; however, she ultimately opted for comfort care with no escalation of treatment. The pleural catheter was removed, and she was discharged to a skilled nursing facility on 2 L of oxygen, with plans for transition to hospice care after discharge home.

The diagnosis

The diagnosis is diuretic-resistant heart failure. Diuretic-resistant heart failure is defined as involving unsuccessful decongestion despite escalating diuretic therapy. The primary goal of diuresis in heart failure is to alleviate symptoms. Diuretic-resistant heart failure, a late manifestation of cardiorenal syndrome, indicates a poor prognosis. It is seen in 20% to 30% of hospitalized patients with advanced heart failure and is caused by neurohormonal activation, renal dysfunction, tubular adaptations, and comorbidities such as chronic kidney disease. Use of high diuretic doses to maintain euvolemia, such as daily furosemide above 80 mg or bumetanide above 2 mg, is associated with a 25% one-year mortality rate.

Guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and other societies recommend nephron blockage and ultrafiltration, advanced therapies such as left ventricular assist devices, or even transplant in refractory cases. Diuretic resistance poses a significant barrier to the medical management of heart failure and often leads to recurrent hospitalizations. Third spacing of fluid is a common complication, as fluid often accumulates in pleural and abdominal spaces and extremities when diuresis is ineffective.

Trapped lung is the formation of a fibrous peel on the visceral pleura preventing lung expansion and can exist as a sequela to lung entrapment caused by an active disease, such as malignancy or infection. Chronic pleural effusions due to heart failure are a relatively uncommon cause of trapped lung, accounting for approximately 5% to 10% of cases, but are seen in up to 20% of cases requiring recurrent thoracentesis. Management options for trapped lung include indwelling pleural catheters, pleuroperitoneal shunts, intrapleural fibrinolytic therapy, and surgical decortication, the last of which is indicated in empyema, hemothorax, or pleural thickening. However, these treatments depend on a patient's ability to tolerate a procedure. While indwelling pleural catheters can offer palliative relief, their efficacy is reduced in cases of trapped lung and they add risks, such as infection. Thus, for patients with diuretic resistance or trapped lung and a poor functional status, a shift toward palliative measures may be the best option.

Pearls

- Transudative effusions secondary to heart failure are treated with diuresis, but treatment effectiveness can be limited by renal function.

- Trapped lung can be a late complication of pleural inflammation in which the lung cannot expand and thus therapies often do not provide subjective relief.

Case 4: Streptococcus dysgalactiae bacteremia complicated by pseudogout

By Bernita Vanessa Sidhu, MD, ACP Resident/Fellow Member; Amrutha Mittapalli, MD, ACP Resident/Fellow Member; and Raya Terry, MD, FACP

The patient

An 83-year-old man with simple psoriasis, treated with adalimumab for over five years, presented with witnessed syncope with no preceding illness. He was found to have a temperature of 39.4 °C and a heart rate of 110 beats/min. A physical exam showed a single linear splinter hemorrhage on his right hallux and was otherwise normal.

An electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm with a QT interval of 405 milliseconds (reference range, 350 to 450 ms). Labs were significant for a white blood cell count of 16,000 cells/µL (reference range, 3,800 to 10,500 cells/µL) with an absolute neutrophil count of 12,900 cells/µL (reference range, 1,700 to 7,000 cells/µL), a lactate level of 1.0 mmol/L (reference range, 0.4 to 2 mmol/L), a serum creatinine level of 1.3 mg/dL (compared to a baseline of 0.9 mg/dL and reference range of 0.7 to 1.3 mg/dL), an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 55.5 mL/min/1.73 m2 (reference range, >60 mL/min/1.73 m2), a blood urea nitrogen level of 20 mg/dL (reference range, 7 to 25 mg/dL), an erythrocyte sedimentation rate greater than 119 mm/h (reference range, 0 to 20 mm/h), and a C-reactive protein level of 64.7 mg/L (reference range, <7 mg/L).

The patient's urine analysis showed 20 to 35 red blood cells per high-powered field (reference range, 0 to 4 cells per high-powered field), no white blood cells, and rare mucus. Tests for COVID-19, respiratory syncytial virus, and influenza were negative. Iron studies showed a ferritin level of 554 ng/mL (reference range, 24 to 250 ng/mL), a serum iron level less than 10 µg/dL (reference range, 35 to 150 µg/dL), and total iron-binding capacity of 182 µg/dL (reference range, 270 to 460 µg/dL). The patient's iron saturation could not be calculated, indicating a mixed anemia of chronic disease and iron deficiency.

Peripheral blood cultures were positive for Streptococcus dysgalactiae in four of four bottles. Contrast-enhanced CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis did not identify a clear infectious source. Given the patient's presentation with sepsis and bacteremia of indeterminate origin, he was started on parenteral vancomycin and ceftriaxone.

Following admission, the patient developed acute monoarticular right knee arthritis and underwent arthrocentesis, which showed 64,492 white blood cells per mm3 (reference range, 0 to 200 white blood cells per mm3) with 54% neutrophils. Cultures confirmed Streptococcus dysgalactiae.

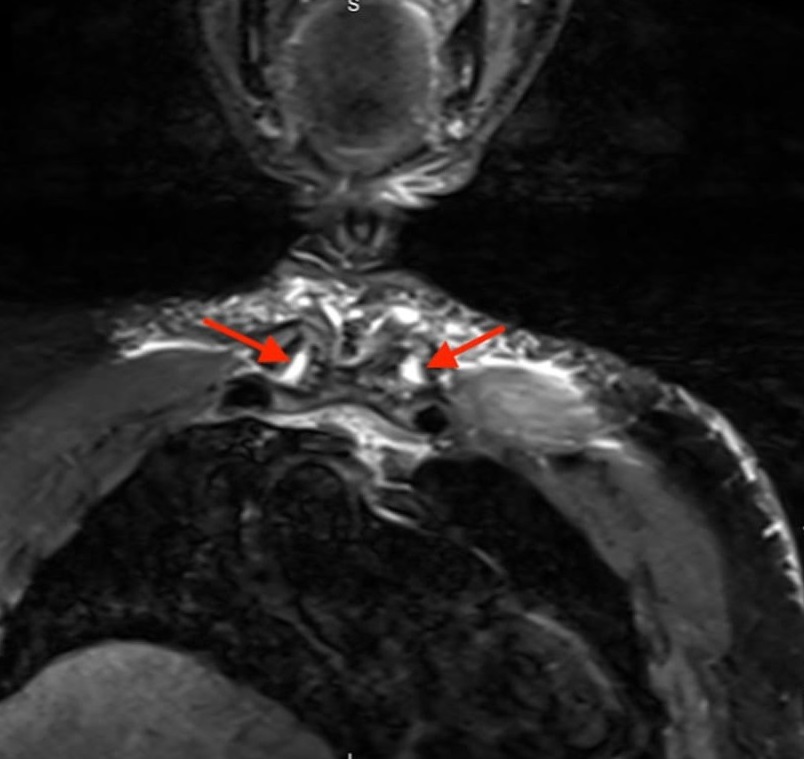

During antibiotic treatment for bacteremia, the patient developed pain in his sternoclavicular (SC) joint. An MRI showed a T2 hyperintense signal representing edema at both SC joints (Figure 5). He underwent washouts of the right knee and bilateral SC joints, and cultures taken from the knee and both SC joints grew Streptococcus dysgalactiae. His repeat blood cultures were clear, and transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiogram showed no vegetations.

Concomitantly, the crystal analysis from the arthrocentesis showed calcium pyrophosphate crystals. Given continued knee pain following washout, the patient received a trial of IV ketorolac, 15 mg every six hours, with 0.6 mg of oral colchicine daily, which improved his pain. The patient was discharged on a six-week course of IV ceftriaxone (2 g daily via peripherally inserted central line), with follow-up scheduled with infectious disease.

The diagnosis

The diagnosis is sepsis secondary to Streptococcus dysgalactiae bacteremia, likely secondary to a skin/soft-tissue infection given underlying psoriatic arthritis on immunosuppressive therapy, complicated by septic arthritis involving bilateral SC joints and right knee and acute pseudogout flare.

Streptococcus dysgalactiae is a gram-positive beta-hemolytic streptococcus commonly found in the genital or alimentary tract, but unlike other streptococcus species, it is rarely found in the mouth. The incidence of bacteremia from Streptococcus dysgalactiae is 16.9 per 100,000, and like other gram-positive organisms, it can cause metastatic infections such as septic arthritis. This particular bacterium is responsible for 12% of cases of streptococcus septic arthritis; in 48% of cases, it causes skin and soft-tissue infection, more rarely pneumonia and meningitis. Septic arthritis of the SC joint represents fewer than 1% of joint infections, typically occurring in patients with pre-existing joint damage or compromised immunity. Being on biologic therapy may increase risk.

Pseudogout, a crystalline arthropathy, deposits calcium pyrophosphate crystals in various joints and is associated with conditions such as thyroid disease, hemochromatosis, and chronic kidney disease. It is only associated with septic joints in 1% to 2% of cases. It affects damaged joints and can mimic osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, or gout. Treatment of pseudogout flares is like that for gout, with NSAIDs as first-line therapy unless contraindicated by heart or renal failure. Colchicine, given initially at 1.2 mg, then 0.6 mg daily, is effective if started within 24 hours. Steroids, either systemic or injected, are also a treatment option but may be contraindicated with concurrent infection.

Pearls

- Addressing bacteremia includes identifying and treating both its source and any sites of metastatic infection.

- A joint is predisposed to infection if there is underlying pathology such as osteoarthritis, trauma, or gout.