Cases from LSU Health New Orleans

Salicylate toxicity, mucormycosis, and more.

Case 1: Chronic salicylate toxicity

By Nikki Arceneaux, MD, ACP Resident/Fellow Member; Pooja Goel, MD; Charlie Woodall, DO, ACP Resident/Fellow Member; and Seth Vignes, MD, ACP Member

The patient

A 71-year-old woman with hypertension, hyperlipidemia, lumbar spinal stenosis, and arthritis presented with slurred speech and encephalopathy that had progressed over one week. At presentation, she was alert and oriented but tangential in conversation with notable dysarthria, hearing impairment, and bilateral lower-extremity weakness. She did not report tinnitus. She displayed severe ataxia on exam, as well as tachypnea with a respiratory rate of 24 breaths/min (reference range, 16 to 20 breaths/min). A CT and CT angiogram of the brain showed no acute findings.

Initial labs were notable for an arterial blood gas with a pH of 7.42 (reference range, 7.32 to 7.42), a partial pressure of carbon dioxide of 18 mm Hg (reference range, 35 to 45 mm Hg), a serum sodium level of 134 mEq/L (reference range, 135 to 145 mEq/L), a serum chloride level of 111 mEq/L (reference range, 96 to 106 mEq/L), and a serum bicarbonate level of 11 mEq/L (reference range, 24 to 30 mEq/L), indicative of mixed disorder with a primary chronic respiratory alkalosis and underlying non-anion-gap metabolic acidosis. Upon targeted questioning, she reported taking more than 15 aspirin powders orally (845 mg each) daily for arthritis pain for the prior three weeks. Subsequently, her salicylate level was found to be 68 mg/dL (reference range, <30 mg/dL). Her urine drug screen and acetaminophen level were negative for other ingestants.

The patient was started on a sodium bicarbonate drip to aid in urine alkalinization. Later in the evening, her mental status declined with increasing somnolence, so emergent hemodialysis was initiated. Over the next two days, her salicylate levels trended down to below 3 mg/dL, after which her bicarbonate drip and hemodialysis were stopped. Her hearing, dysarthria, and gait imbalance improved by hospital day 3, and she was discharged to a skilled nursing facility.

The diagnosis

The diagnosis is chronic salicylate toxicity. Compared to acute salicylate toxicity, chronic salicylate toxicity results from repeated overmedication that occurs over days to weeks with gradual symptom onset. It is therefore found predominantly in older patients with increased medical comorbidities, in contrast to acute toxicity. The classic triad for salicylate toxicity is hyperventilation, tinnitus, and vomiting, but symptoms can include nausea, abdominal pain, agitation, slurred speech, hearing loss, coma, and seizures. In chronic salicylate poisoning, symptoms may be triggered by lower plasma levels of salicylate compared to acute poisoning. This is often due to the drug being stored in peripheral tissues, including the central nervous system, after repeated exposure. Thus, relying on serum measurements can lead to underestimation of severe toxicity and delay appropriate treatment.

Physical exam findings are notable for tinnitus, hearing loss, tachypnea, tachycardia, hyperthermia, generalized abdominal pain, generalized weakness, altered mental status, and gait instability. Classic laboratory findings are a mixed acid-base disorder, usually highlighted by respiratory alkalosis and anion-gap metabolic acidosis. In this case, the finding of chronic respiratory alkalosis alerted the team to inquire about salicylates, since the differential diagnosis for chronic respiratory alkalosis is narrow. This case highlights the continued importance of acid-base evaluation in medical diagnostics.

Urinary alkalinization is a key element in the management of both acute and chronic salicylate toxicity. Increasing the urine pH to a level higher than the blood pH traps salicylate in the tubular lumen and increases urinary excretion. Hemodialysis is indicated in severe salicylate toxicity, evidenced by severe clinical manifestations, such as coma, respiratory depression, or seizure, or a serum salicylate level above 90 mg/dL.

Pearls

- Assessment of severity of salicylate toxicity should consider clinical signs, serum salicylate concentration, and acid-base status, as serum levels alone may underestimate severity in cases of chronic toxicity.

- For mild to moderate toxicity, bicarbonate infusion should be administered to alkalinize urine, thus increasing urinary salicylate excretion.

Case 2: Parkinsonism-hyperpyrexia syndrome

By Hannah Rader, MD, ACP Resident/Fellow Member; David Nguyen, MD; Brian Coe, MD, ACP Resident/Fellow Member; Maren Bell, MD; Hina Qureshi, MD, ACP Resident/Fellow Member; Michael Olejniczak, MD, ACP Resident/Fellow Member; and Ross McCarron, MD

The patient

A 67-year-old man with Parkinson's disease, hyperlipidemia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and depression presented to the ED with reports of confusion and generalized weakness persisting for two days after an unwitnessed fall. The patient's medications included amantadine, carbidopa/levodopa, and pramipexole, but his wife reported that he had not been taking them for the past three days. Shortly after arrival, the patient developed acute encephalopathy, hypertensive emergency (171/94 mm Hg), tachycardia (112 beats/min), and fever to 104°F.

Admission labs were notable for a serum sodium of level of 130 mEq/L (reference range, 135 to 145 mEq/L), a serum chloride level of 100 mEq/L (reference range, 96 to 106 mEq/L), a serum bicarbonate level of 16 mEq/L (reference range, 24 to 30 mEq/L), a lactic acid level of 2.5 mmol/dL (reference range, <2 mmol/dL), and a creatine phosphokinase level of 19,351 units/L (reference range, 50 to 175 units/L). Initially, the patient's presentation was thought to be due to infection, so he was started on empiric antibiotics and antivirals for meningoencephalitis coverage (vancomycin, ceftriaxone, ampicillin, and IV acyclovir) and blood cultures were obtained.

The patient developed significant diffuse muscle rigidity, most notably in his extremities, during his first 24 hours of admission, along with continued high-grade fevers and altered mental status. Infectious workup including blood cultures, urinalysis, and a chest X-ray were unrevealing. Antibiotics were discontinued on hospital day 2 and he was diagnosed with Parkinsonism-hyperpyrexia syndrome, resulting from the abrupt discontinuation of his home medications. He was restarted on his home Parkinson's medications in a slow stepwise fashion and treated with dantrolene, antipyretics, and cooling blankets. Following reinitiation of all his home medications, the patient had rapid improvement in rigidity, fevers, and tremor. With the assistance of physical and occupational therapy, he recovered near to his prior baseline physical functioning.

The diagnosis

The diagnosis is Parkinsonism-hyperpyrexia syndrome (PHS). PHS is a rare (reported incidence of 0.3%) but potentially fatal (reported mortality of 4%) complication of Parkinson's disease that can often be overlooked because of its similarities to other life-threatening illnesses, such as neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) and meningoencephalitis. The first signs of PHS are often fever and hypertension, which carry a wide differential, so clinicians must have a high degree of suspicion in any febrile patient with Parkinson's disease and altered mental status. Medication cessation or nonadherence is the most common precipitating factor of PHS (responsible for 46% in a large case review series), but it can also occur secondary to initiation of dopaminergic medications or deep brain stimulator malfunction (13%).

Given the clinical similarity between PHS and other acute dysautonomias, such as serotonin syndrome and NMS, medication history is crucial in diagnosis. Case reports have identified several interventions that can reduce autonomic instability, fevers, and rhabdomyolysis, including dantrolene, cooling blankets, IV hydration, antipyretics, and reversal of the underlying trigger such as resuming home medications or repairing a malfunctioning deep brain stimulator device. Mortality in PHS is driven by aspiration pneumonia, acute renal failure, and thrombotic complications. Approximately a third of patients have some degree of permanent neurological sequelae, such as increased rigidity, bradykinesia, postural instability, cognitive decline, and autonomic dysfunction.

Pearls

- Suspicion for PHS should be high in any patient with Parkinson's disease and autonomic instability and fever, particularly in the setting of abrupt cessation or dose reduction of Parkinson's disease medications.

- Treatment of PHS includes medication management, physical and occupational therapy, and supportive care to decrease risk of permanent sequelae.

Case 3: Mucormycosis

By Nali Gillespie, MD, ACP Resident/Fellow Member; Hannah Rader, MD, ACP Resident/Fellow Member; Thomas Deiss, MD; Kyle Hoppens, MD; and Michael Modica, MD, FACP

The patient

A 60-year-old woman with hypertension, cocaine use, bilateral cataracts, and type 2 diabetes with associated retinopathy presented with one week of worsening right facial pain, right eye pain, and blurry vision. She reported difficulty taking her home medications, including insulin, due to vision issues. Over the prior month, she had presented to multiple hospitals for similar symptoms. During one of these visits, she was found to have acute sinusitis based on CT imaging of the orbits, revealing mucosal thickening in the right paranasal and maxillary sinuses. She was prescribed antibiotics for presumed bacterial sinusitis and discharged but never filled the prescription.

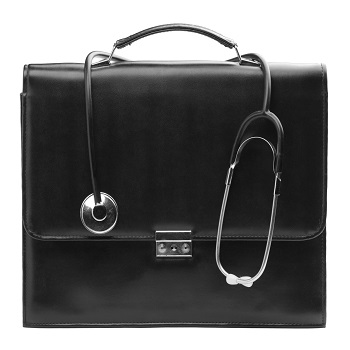

At presentation, her blood glucose level was 478 mg/dL (reference range, 70 to 110 mg/dL) without diabetic ketoacidosis. Her hemoglobin A1c level was above 14% (reference range, 4.0% to 5.6%). Repeat CT imaging showed worsening sinusitis, with osseous changes suggestive of cortical breakthrough (Figure 1). Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid was initiated.

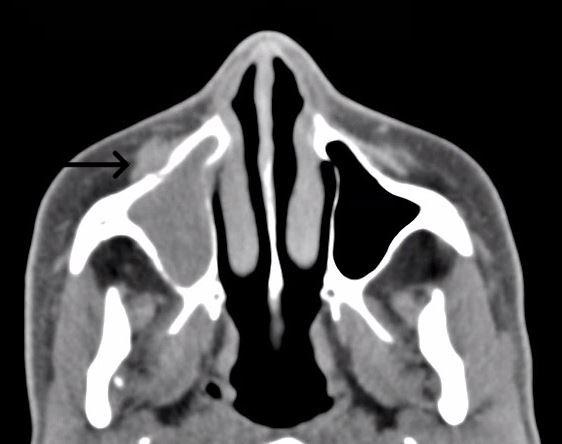

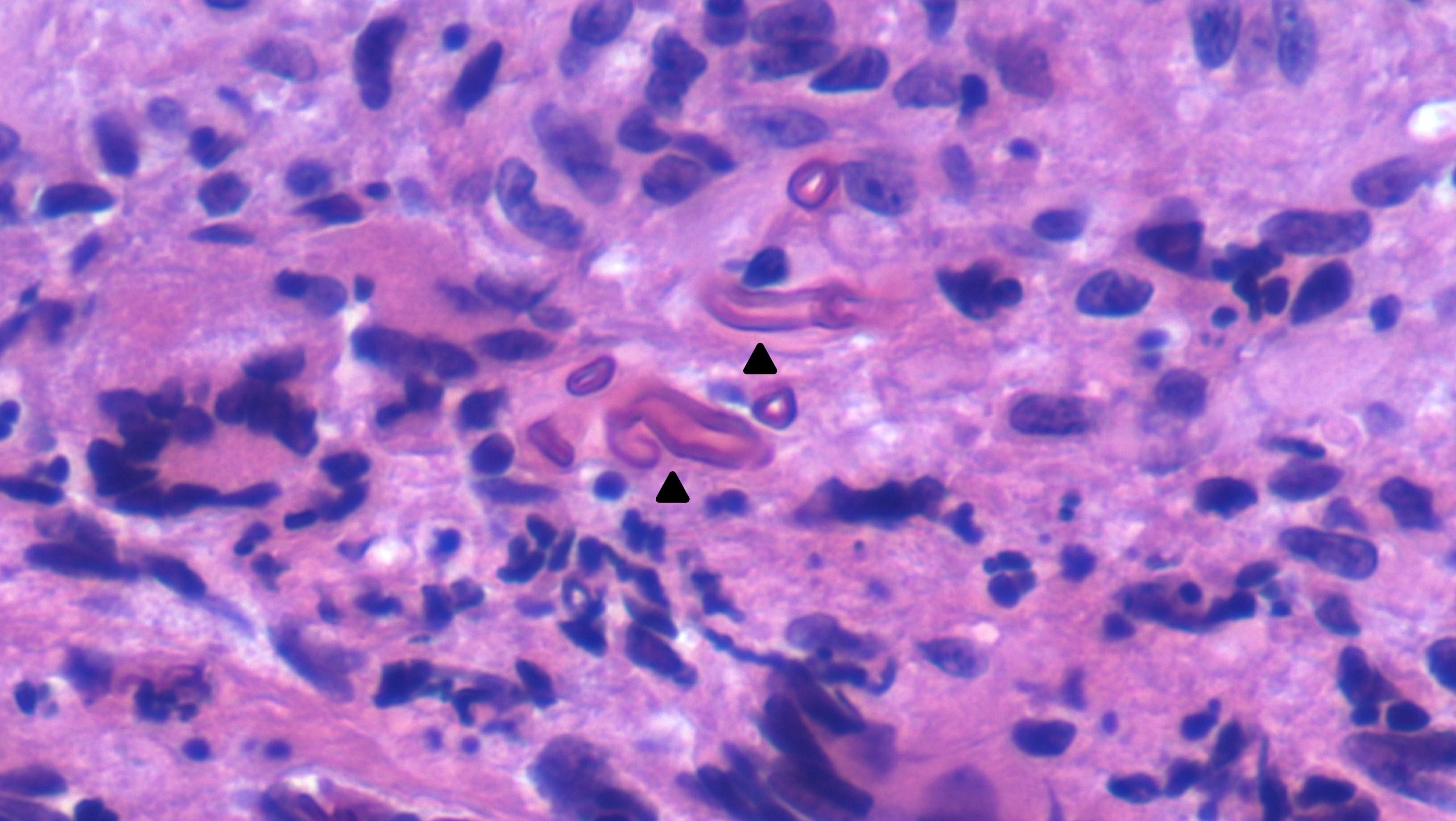

MRI of the orbits the following day revealed areas of necrosis involving the maxillary sinus, ethmoid air cells, nasal cavity, and right frontal sinus, concerning for acute invasive fungal sinusitis (Figure 2). She was transitioned to broad-spectrum antibiotics (vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam) and antifungals (voriconazole) and had an endoscopic sinus evaluation by otolaryngology. She was found to have necrotic right maxillary, ethmoid, and frontal sinus infections. Cultures grew methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Fungal cultures were negative. Pathology review showed granulomatous inflammation and hyphae concerning for mucormycosis (Figure 3). She was treated with vancomycin, cefepime, and amphotericin B for two weeks, then de-escalated to posaconazole.

The diagnosis

The diagnosis is rhino-orbito-cerebral mucormycosis complicating bacterial sinusitis in the setting of uncontrolled type 2 diabetes. Epidemiologically, mucormycosis is rare and its exact incidence is unknown, but it is mostly associated with diabetes (32% to 75% in a recent meta-analysis), followed by hematological malignancy (11% to 44%), hematopoietic stem-cell transplant (1% to 11%), solid organ malignancy, solid organ transplant, trauma, HIV, prolonged corticosteroid use, autoimmune disorders, and idiopathic causes (0% to 2% each). Mucorales infections with uncontrolled diabetes classically result in rhino-orbital-cerebral infection. The pathogenesis of mucormycosis in uncontrolled diabetes is due to the presence of ketone reductase enzyme in Rhizopus organisms, which allows rapid growth in high glucose and acidic environments. Sinusitis in the presence of diabetic ketoacidosis should raise the clinical suspicion of mucormycosis.

Common presenting findings for mucormycosis are fever, nasal ulcerations, facial swelling, vision abnormalities, and ophthalmoplegia. Diagnosis is based on histopathological identification with subsequent culture confirmation. However, culture identification is often technically difficult and lacks robust sensitivity, so empiric treatment is often necessary. Available serum fungal tests such as 1,3-beta-D-glucan and Aspergillus galactomannan assays have no shared cell wall components with Mucorales species and therefore will not be positive in mucormycosis.

The standard course of treatment is early initiation of the lipid formulation of IV amphotericin B, coupled with surgical debridement of all necrotic tissue. If there is a high degree of clinical suspicion, antifungals should be initiated before the diagnosis is confirmed. Prompt initiation of antifungal treatment is key given the condition's virulence and associated mortality rates (44% to 80%). Patients can be transitioned to oral antifungal agents after signs of clinical improvement (improvement in radiographic disease appearance, sinusitis symptoms, and underlying diabetes control) with amphotericin B, usually after two to four weeks. Stepdown therapy with oral posaconazole or isavuconazole should be continued until clinical and radiographic evidence of active disease has resolved, which can take months but can be lifelong in cases of ongoing immunosuppression.

Pearls

- Suspicion for mucormycosis should be high in patients with uncontrolled diabetes and nonresolving sinusitis.

- Mucormycosis is treated initially with high-dose amphotericin B for several weeks, followed by prolonged stepdown therapy with oral posaconazole or isavuconazole.

Case 4: Light-chain amyloidosis

By Humza Malik, MD, ACP Resident/Fellow Member, and Seth Vignes, MD, ACP Member

The patient

A 60-year-old man with a history of prostate cancer in remission, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and coronary artery disease presented with an enlarged tongue, unintentional 80-lb weight loss over one year, and new facial swelling over three days. Vital signs were notable for a blood pressure of 95/55 mm Hg. Heart rate was 85 beats/min. Physical exam revealed lower-extremity edema, periorbital edema and purpura, and macroglossia.

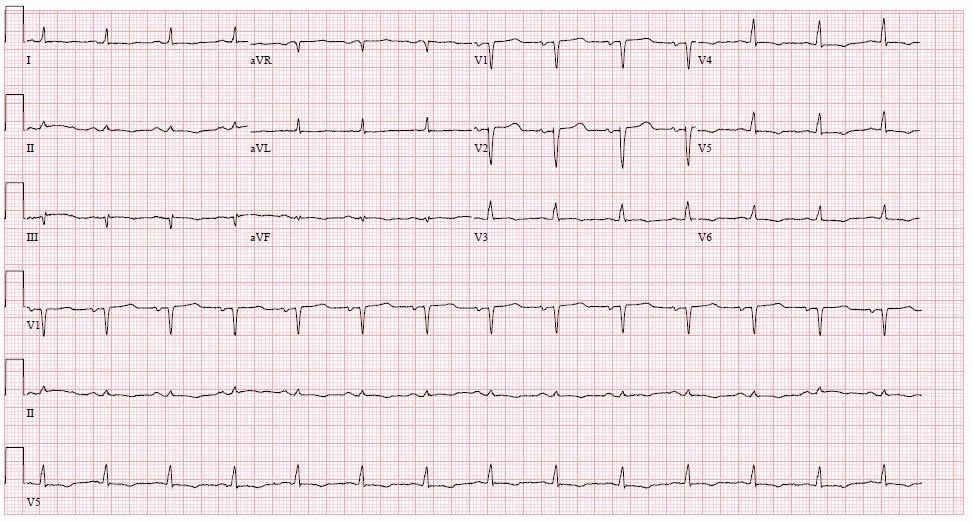

Laboratory evaluation was notable for leukocytosis of 17.4 × 103/µL (reference range, 4 to 10 × 103/µL) with neutrophilic predominance (92%; reference range, 32% to 64%), and elevated levels of C-reactive protein level at 11.1 mg/dL (reference range, <1 mg/dL), high-sensitivity troponin at 52 ng/L (reference range, <45 ng/L), and B natriuretic peptide at 1,587 pg/mL (reference range, <100 pg/mL). A urine dipstick showed 3+ protein (reference range, negative). An electrocardiogram was notable for low voltage (Figure 4).

Free light chains returned with a kappa to lambda light-chain ratio of 0.08 (reference range, 0.26 to 1.65), serum protein electrophoresis showed no monoclonal peaks, and urine protein electrophoresis showed abnormal light chains unassociated with heavy chains. An echocardiogram revealed a depressed ejection fraction of 40% to 45% as well as markedly increased left and right ventricular wall thickness (Figure 5). A technetium-99 pyrophosphate scan was negative.

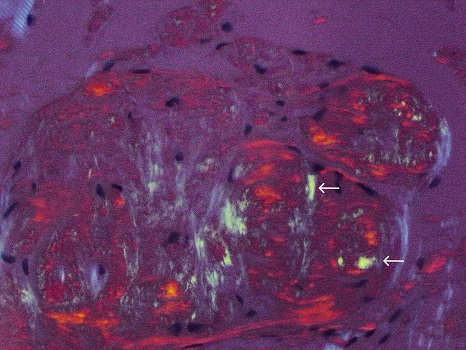

On hospital day 3, a tongue biopsy was positive for apple-green birefringence under polarized light with Congo red staining (Figure 6). Bone marrow biopsy was not recommended as the patient's age and heart failure would make autologous stem-cell transplant unlikely. The patient elected to pursue the remainder of his treatment in his hometown.

The diagnosis

The diagnosis is immunoglobulin light-chain amyloidosis. Immunoglobulin light-chain amyloidosis is an aggressive and irreversible infiltrative disease characterized by the deposition of insoluble amyloid fibrils in multiple organ systems, most commonly the bone marrow, kidneys, heart, and tongue. Immunoglobulin light-chain amyloidosis is difficult to diagnose given its clinical heterogeneity and overall rarity. A survey of over 500 patients with immunoglobin light-chain amyloidosis found that the time from initial symptom presentation to diagnosis was two years. Incidence of disease is estimated at 10 to 14 per million per year, with a higher prevalence in men. At the time of diagnosis, 71% of patients have cardiac involvement, 58% have renal involvement, 23% and neurological involvement, 16% have liver involvement, and 15% have skin and soft-tissue involvement. Macroglossia and periorbital purpura are seen in 10% to 15% of immunoglobin light-chain amyloidosis cases. Immunoglobulin light-chain amyloidosis is more commonly diagnosed following discovery of nephrotic-range proteinuria, heart failure with multi-chamber enlargement and increased wall thickness, nondiabetic neuropathy, a low-voltage QRS on electrocardiogram, or unexplained hepatomegaly.

Diagnostic criteria of immunoglobulin light-chain amyloidosis includes 1) presence of end-organ amyloid involvement (heart, renal, liver, peripheral nerves) not thought to be due to any alternative cause (such as hypertension or diabetes); 2) positive amyloid staining on electron microscopy; 3) light-chain predominance on spectrometry, staining, or microscopy; and 4) evidence of a monoclonal plasma cell proliferative disorder by light-chain or serum protein electrophoresis evaluation. Autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation and bortezomib-based chemotherapeutic regimens are first-line therapies. The prognosis of immunoglobulin light-chain amyloidosis is very poor, with 20% mortality at six months, driven in large part by delayed diagnoses and multiorgan involvement, especially cardiac and renal sequelae.

Cardiac amyloidosis is differentiated into two major subtypes: cardiac amyloid light-chain, such as in our patient, and transthyretin-related cardiac amyloidosis. Differentiation between the two is achieved via light-chain evaluation and technetium-99 pyrophosphate scanning. Early delineation between subtypes is crucial given the different treatment modalities available for each. Amyloidosis-related heart failure with reduced ejection fraction is associated with poor response to guideline-directed medical therapy, especially beta-blockers and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors, due to hypotension and cardiogenic syncope associated with advanced amyloidosis, and retrospective research has shown no mortality benefit in such patients.

Pearls

- Macroglossia is a characteristic finding in immunoglobin light-chain amyloidosis and may be accompanied on exam by periorbital purpura.

- Amyloidosis-related heart failure does not respond well to guideline-directed medical therapy, especially beta-blockers and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors.